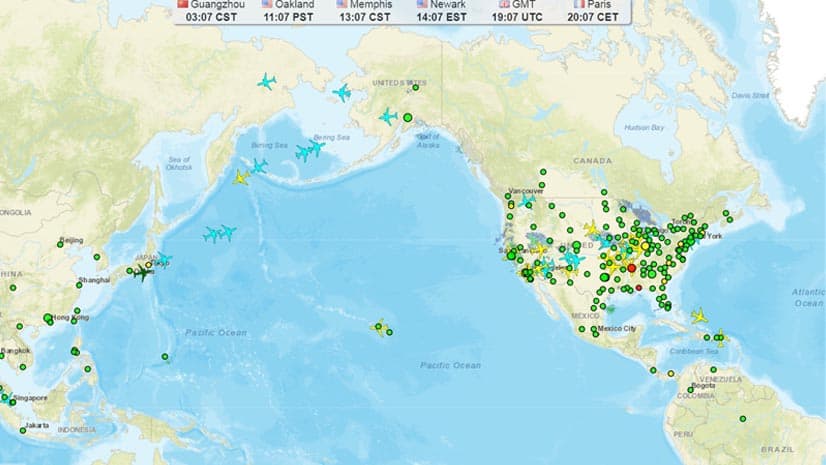

It was late on a Thursday afternoon in November and FedEx had 160 jets in the air, flying to destinations around the globe. Most were on schedule, though a few were running several minutes late.

Each craft carried a bay full of items for eager customers from Shanghai to Memphis, Lisbon to San Francisco. Some of those packages actually included replacement parts for planes around the globe, and their on-time delivery was crucial to the carrier’s success.

Mark Yerger, vice president of material management at FedEx Express, knew where the grounded planes were and where to find the proper parts for them because of a sophisticated geographic information system (GIS). Through the system, Yerger could track up-to-the-minute progress for the fleet’s 386 jet aircraft and, with a click or two on his computer or hand-held device, drill down to learn just about anything he needed to know about a particular flight.

That level of spatial awareness, or location intelligence, empowers Yerger and team to maintain an impressive level of airplane health and availability. Last year, for instance, just 60 FedEx flights out of approximately 240,000—or .025%—failed to take off within 15 minutes of scheduled departure time because a replacement part wasn’t available in time.

Five Ps of Efficient Service

Yerger’s main concern is the operational status of hundreds of FedEx planes—and the parts that ensure their readiness. Those parts range from rivets that cost pennies to engines that cost millions of dollars. For an operation on the scale of FedEx to run cost-effectively, it can’t stock every part in every airport around the world. Instead, Yerger and his team rely on location intelligence to guide decision-making about parts and planes.

He describes their daily task as orchestrating a “very large aerial ballet” to ensure that the correct parts reach the correct planes quickly and efficiently. That choreography, he says, would be virtually impossible without the GIS-based smart maps at the heart of the FedEx tracking system.

Yerger uses five Ps to explain the ballet. “I have to have a part, a person, a plan, and a plane all in the same place at the same time,” he says.

To do that, Yerger often places a needed part on a FedEx jet that is carrying its usual cargo and is headed to the same location as the aircraft in need of repair. He can make that call by finding the correct part and then coordinating its delivery with flights in the air, or about to take off.

“If I can get that data in a very easily digestible way quickly, then I’m not going to make fire-drill calls,” he says. That often means he can avoid a last-minute rerouting or a “deadhead” flight that carries nothing but the replacement part. Those flights burn pricey fuel and pilot hours—without moving customer packages one mile.

Collaborating with IT

Yerger relies on a program FedEx has built and refined over the years, overseen by Bob Minford, the company’s vice president of airline technology. The program integrates GIS technology with the FedEx maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) system, delivering location intelligence on smart maps. The program is available to FedEx executives, pilots, mechanics, flight planners, and just about anyone at the company involved in getting goods to their destination.

“Because of our scale and the global nature of our business,” Minford says, “we have a large number of our team members that are looking at this data.”

In order to deliver the world on time, those FedEx professionals need information quickly. “Whether they’re sitting in Global Operation Control managing all the operations, in Maintenance Operation Control, or at a maintenance shack waiting for a plane to come in, this gives them visibility” into the locations and dependencies among parts, people, and planes, Minford says. “It ties those relationships together by bringing all those disparate data sources into much better information [so] that they can make good decisions.”

That means mechanics can tap into the system using an iPad while in the hangar inspecting or working on a plane. “They could see all the manuals,” Minford says. “They could see everything about that aircraft, but they can also do every transaction that they can do on the desktop. So we’ve extended those capabilities from the desktop out to mobile devices.”

The bottom line, Minford says, is that the program allows our partners to concentrate on what’s most important.

“[W]ith the scale that we’ve gotten to and how these planes are constantly in the air, the geospatial tools really help many facets of the business to manage and to ensure that we simplify things.” That, he says, enables FedEx to “focus on the things that we have to focus on from a safety and an on-time service perspective.”

Having timelier access to more granular information, having the problems jump out of the screen… means that my maintenance specialists can absorb much more information more quickly than by looking at giant spreadsheets.

Mark Yerger, VP of material management at FedEx Express

Customers Want Speedy Delivery

“When it absolutely, positively has to be there overnight,” a FedEx tagline first deployed in 1978, has never been more apropos in the delivery and logistics business than right now.

While consumers still shop mostly in stores, the balance is shifting. The percentage of goods ordered online continues to grow, and with it, expectations for fast—sometimes even same-day—delivery.

That demand led to a 17 percent spike in parcel volume during 2017, according to a Supply Chain Dive article. Additional double-digit gains were predcited through 2020 across more than a dozen major economies. FedEx connects with 99 percent of the global GDP through 14 million air and ground shipments each business day.

Retail sales, one of the financial drivers of parcel companies, were estimated to rise almost 5 percent in 2018 over 2017’s nearly $5.7 trillion, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

If global trade skirmishes escalate into trade wars this year, that could put a crimp on commerce. But the long-term trend is toward more goods being delivered quickly all around the world.

Long Haulers to Short Hoppers—Coordinating Moving Targets

Regardless of politics and trade negotiations, certain FedEx officials spend the majority of their day ensuring that the company’s fleet of almost 700 jets—ranging in size from long haulers like the Boeing 777 to smaller mid-range jets—are ready to fly around the clock.

Yerger relies on the company’s location intelligence system to track the fleet and make sure planes are where they are supposed to be, safely and at the right time. That’s no small feat when FedEx has aircraft circumnavigating the earth 20,000 times each month.

Coordinating FedEx maintenance worldwide with location intelligence

Like any executive who must make sensitive decisions in short order, Yerger looks to the GIS-powered system to find signals in the noise. As he explains, “The computer and the picture tell you what your biggest worries are, and/or what your easiest solutions are in a way that’s much easier for a human to digest.”

Planes on time, for instance, appear in green on his smart device or desktop, while those that are lagging are red. He can see flights all over the earth in one glance, or limit his view to aircraft associated with a particular region or airport.

That flexibility saves him and his fellow managers, as well as the mechanical staff that reports to him, precious minutes for other pressing decisions.

Data to Save Time

In essence, the FedEx system replaces a slew of documents with an integrated smart map, Yerger says.

“I don’t have to go thumb through 130 or 140 lines of a spreadsheet to figure out when did [the flight] depart, when was it supposed to depart, what’s the turnaround time, what’s the window, and when it’s expected back to [FedEx headquarters in] Memphis,” he explains.

One of Yerger’s primary responsibilities is avoiding the dreaded and costly AOG—an aircraft on the ground, unable to fly. During that November afternoon, Yerger checked the system to discover that only two of the planes in the air were behind schedule enough to cause concern. Both needed repairs that might not be completed in time for the scheduled departures. As a result, other planes might have to be used as replacements. In the industry, that’s called a tail switch.

On paper, the variables involved in the aerial ballet seem overwhelming. For instance, not all repairs are created equal. Some are mission critical and must be made before the airplane can lift off again. Others are less pressing, giving Yerger and team the luxury of time.

Then there are the parts themselves. FedEx manages more than 80,000 part numbers across its air operations. It keeps at least one part in each of about 575,000 bins at airports worldwide. Its nearly 700 planes visit 175 airports worldwide.

When one of those planes needs repairs and the five Ps aren’t aligned, Yerger’s team uses the logistics system to find the correct replacement part and coordinate its delivery to the aircraft’s next stop. Yerger likens the process to passing a hockey puck where a teammate will be instead of where he is.

To meet that “moving demand,” FedEx annually sends more than 850,000 shipments of parts. It’s a massive job made faster and more reliable by location intelligence.

When I think about GIS, I think about a couple variables—not only [the] location of our aircraft, but GIS also provides us with time. And those are two variables that are extremely important to the business at FedEx.

Bob Minford, FedEx VP of airline technology

Artificial Intelligence Predicts Maintenance Needs

Yerger, Minford, and their FedEx colleagues know as well as anyone how important speed is to customer satisfaction and competitive advantage. The location intelligence system they rely on was built to help them make the right decisions faster.

And despite its success, FedEx continues to find ways to wring idle minutes out of its operations. The constantly evolving system, Minford says, now incorporates artificial intelligence, or AI, that forecasts when a plane needs replacement parts or a maintenance checkup.

AI’s predictive capabilities, combined with the geospatial programs that monitor where a plane is, amount to “almost the holy grail for a maintenance operation,” he says.

The company is also exploring maintenance innovations like using drones to perform airplane inspections that are cumbersome for humans to undertake. The top of a 777’s tail, for instance, can stand 60 feet above the ground. A mechanic piloting a drone with high-definition cameras now can detect hail or lightning damage faster than ever, while standing on the tarmac.

“As new things come up, we can just layer those relationships on,” Minford says, “and the map visualization simplifies it so that humans can understand it.”

That awareness of information tied to time and location, he says, allows Yerger and other FedEx professionals to act quickly on issues flagged by the system. “But they also see the big picture,” Minford adds.