Blog Archives

Post navigation

BP Shares Eight Lessons on Digital Transformation

An inside look at BP's digital transformation, with lessons on successfully deploying enterprise software.

Leaders of Fortune 500 companies believe digital transformation is the future of their business. According to Forbes Insights, half of senior executives worldwide, when asked about digital transformation, said that the next two years will be “critical for their organizations in order to make this transition and prepare for future opportunities.”

Here at BP, that means embracing new technologies, including digital, which will improve our ability to monitor, predict, and optimize our business. Ultimately, this digital transformation will enable BP to create more sustainable operations, better manage expenses, and uncover new products and services for customers around the world.

Enacting digital transformation on a global scale is a vast undertaking at BP, a company of more than 70,000 employees dedicated to oil and gas exploration, production, transportation, refining, and retail—with airline and shipping divisions and a growing presence in biofuels and wind energy. Along the way, we’ve learned several valuable lessons that we’ll share here.

At BP, digital transformation takes many forms. We’ll explore it through the lens of location intelligence, which is critical to our business. Location intelligence helps BP professionals track the location and condition of assets; understand in real time the events that shape the regions and neighbourhoods where we operate; and identify areas of customer need and business growth.

In short, location intelligence helps us make smart business decisions across the globe.

Becoming a digital energy company required us to overhaul our location intelligence capabilities, and central to that transition was modernizing our geographic information system (GIS) capabilities. The lessons we learned during that implementation—detailed throughout this article—are worth considering for any company that enlists enterprise software to support digital transformation.

Lesson 1: Embrace the enterprise platform

Location intelligence—and the GIS technology that underpins it—has long been crucial to BP’s business. Members of our exploration team use GIS-based maps to plot roads and design new access routes. Our environmental teams use GIS to create impact assessments, while our project teams leverage it to help design and deploy construction projects. GIS is the working geospatial brain that delivers the digital maps and analysis we need to help run a sustainable energy business.

The Fruits of Digital Transformation

For a look at how other companies are driving business advantage from digital transformation, visit this e-book.

As we set out two years ago to build a new foundation for location intelligence at BP, we systematically embraced an enterprise platform approach to GIS instead of building self-contained solutions for each business case. We wanted our experience with GIS to be similar to our experience with other enterprise technologies.

Over the years, numerous instances of GIS had taken root independently at BP. Businesses had various levels of GIS deployments, and some GIS tools had been built for specific workflows. But all were created at different times, by different teams, with different purposes, and we found ourselves with disconnected data and workflows. We had to support, maintain, and migrate multiple software versions almost constantly, and our total cost of ownership was excessively high.

Adopting a true platform approach has helped reduce those costs. But cost was just the beginning of the benefits. For BP and other companies, an enterprise platform pays dividends in numerous ways:

- The platform delivers faster time to value. BP professionals want decision-support tools that adapt to their changing needs. With an enterprise GIS platform, we can more easily build mapping and analytics apps at the speed of business—in fact, we enable business users themselves to configure lightweight apps rather than enduring longer software development cycles from a central team. By letting the users create the tools they need, a business can quickly convert data and information into insights.

- An enterprise platform speeds up collaboration. For illustration, we can look at BP’s pipeline team, which uses GIS as the system of record on the physical hardware of our pipelines, with details that include the equipment’s size, metal composition, age, and more. The pipeline team also manages conditional data꞉ the type of soil or water nearby, the pipeline’s maintenance history, and more. Others in Upstream also need access to portions of this information, and if those teams are working on separate systems, additional effort is required to export, translate, and load data from one system to the others, which can take hours or even days. When they’re on an enterprise GIS platform, those two teams can share the same location intelligence immediately, leading to quicker access, efficient analytics, and more informed decisions.

- The platform creates a virtuous cycle for geospatial information. We’ve seen many instances where a dataset that was considered basic information for one team turns out to be very valuable to another team. For instance, activities that we track in our Upstream business turned out to be very valuable intelligence to our Downstream teams. These two parts of the business may otherwise have had limited interaction. But with shared data on a common GIS mapping platform, users are now able to see the data resources available and use information from other teams. As a result, traditional organizational siloes have started to dissolve. That, in turn, has led to new efficiencies, insights, and business opportunities. We see this happening across teams and geographies.

In the enterprise platform, we give each business entity its own space to manage its data, workflows, analytics, and publishing. As a result, data and information are more accessible across the organization, leading to more opportunities to collaborate. This drives more value from each dataset and creates the virtuous cycle of new capabilities and opportunities that may have been missed.

For these reasons and more, we believe providing a company-wide geospatial platform—rather than building specific solutions—will lead to more sustainability and a larger return for an organization. The additional lessons below explain some of the learnings and best practices we have found while creating a successful and sustainable location intelligence system.

Lesson 2: When you’re everywhere, you’re nowhere

Location intelligence and GIS technology are leveraged across BP, and this diverse use creates a paradox that companies often experience with other enterprise technologies: because the technology is needed everywhere, it is owned nowhere.

Historically in many companies, the IT department—because it serves all the company’s businesses—has stepped in as the foster parent for enterprise software platforms. While this has been a successful model for enterprise tools with defined access and workflows, the model does not work as well for platforms with an open data structure and a nearly unlimited set of use cases.

BP’s Lessons on Digital Transformation

- Embrace the enterprise platform

- Find the right home

- Set your data free

- Let business users extend the platform

- Tailor user support to the new paradigm

- Automate

- Mind your marketing

- Measure success

An enterprise platform, by definition, is a tool that can be used in many ways. In the case of a geospatial platform, the use cases are especially diverse. At different times and for different parts of the business, the platform can act as a system of record, a system of engagement, and a system of insight. In light of this, we believe a location intelligence platform should be placed in the business function as close to the core business as possible, where they benefit from in-depth business knowledge, workflow understanding, geospatial data skills, and competence in the toolkit.

Regardless of where the platform is hosted, deep collaboration with the Information Technology and Systems (IT&S) organization is still crucial in delivering the technology platform. IT&S helps us deploy the right hardware, architect the most efficient system design, manage network and storage needs, and take care of the software portfolio.

As we implemented our location-based platform, we relied on a virtual geospatial project team composed of IT&S and business professionals to increase engagement, communication, and collaboration.

Deciding which part of the business organization should take ownership of the geospatial capabilities will be different for almost every company due to organizational structure, primary user groups, budgetary capabilities, and other concerns. For BP, the GIS platform found its initial home in the subsurface business under the Upstream segment.

Lesson 3: Set your data free

While the platform approach creates new opportunities by making data formats and services interoperable between our teams and functions, it also introduces new collaboration challenges.

BP has always had a mix of confidential data in our work. Historically, we have locked access to much of our data, either because of limitations in the technology or a “better safe than sorry” approach. Unfortunately, this resulted in duplication of data across projects and teams.

In the geospatial domain, this becomes a sizable issue. We found multiple files for the same pipeline locations, the same wells, etc. We also found subtle changes within some of the files. In many cases, the person who made the copy of the data moved on, and the team continued to use the information, assuming it was the most current version. This is not ideal in any digital transformation.

At BP, the reality is that 95 percent of the geospatial data we use can be shared across the entire organization; only a few key datasets need to be locked down. The solution was to challenge the status quo and open all data by default, allowing it to be available and shareable for multiple teams and diverse workflows. This helped power the virtuous cycle of use. Our advice to other executives is to lock down processes and data where required but leave the rest open to provide plenty of room for exploration and innovation. This is what drives new workflows, insights, and the greatest value from the enterprise platform.

That said, we needed to consider how to present data in the right way to help users of the open platform find the most appropriate information for their use case. This is an evolving effort. The solution for now is to tag “admin” items and encourage the use of metadata elements. Simple summaries and basic data quality metrics help ensure that users are more informed when making data choices. This leads to the next lesson: Let your users get their hands dirty.

You need to win user trust and acceptance quickly—don't just throw them an enterprise platform and say 'go.' Orient them first, because trust is easy to lose and exponentially harder to regain.

Brian Boulmay, BP

Lesson 4: Let business users extend the platform

Several years ago, when our GIS provider Esri predicted that our users would soon be able to create targeted apps for many of our location intelligence needs, I was sceptical. At that time, the thought of an end user being able to create apps seemed impossible, but now this is exactly what we see happening. This evolution is enabling almost anyone to build apps and workflows faster than we could produce in a central team, and this is making our business smarter and faster than ever.

Through today’s digital software platforms, app development is lightweight, code free, and user driven. This means business users acting as “citizen developers” can configure the platform to perform analytics and create insights at the pace of business. When all your professionals have the access to configure what they need, the value to a company grows exponentially.

This capability demanded another significant change in how we deploy and support GIS technology here at BP. We have truly opened the platform to our entire company. As we began the rollout, we gave business users a basic orientation on how to configure and create apps and then said, “Here’s the playground. Do what you need to do to solve your business problems.”

They responded eagerly. We are seeing hundreds of maps, apps, and dashboards emerge across our platform, many of which would only have been possible—under the prior way of working—after a user manually retrieved and reviewed various paper and/or digital projects and maps.

This is a powerful example of how our users are configuring location intelligence apps to make better decisions. When that is scaled across tens of thousands of employees, the results are a diversity of ideas, an informed focus on integrated business workflows, gains in productivity, reduced risk, and business agility.

The One Map platform facilitates this on a daily basis. And yet there is a lesson lurking on the flip side of that revelation: Once business users begin creating their own apps, the support team must keep up with them, not vice versa. Mindful that users can quickly lose trust in software platforms that don’t support their needs, we needed to make another significant change in our approach, and this leads to the next lesson: Supporting an enterprise platform.

Lesson 5: System and user support in this new paradigm

Typically, when a company deploys a software solution, the deployment team relies on an install manual and a standard database and format. The setup usually includes a support desk for users, with a few scripts to follow for common workflows. In the worst-case scenario, a vendor support desk might be needed to help with a software issue or tough workflow definition.

In the case of a geospatial platform, there is none of that. Instead, there are different levels of technology, various platforms to deploy on, a massive and diverse set of unknown workflows, and numerous data formats to oversee. Different versions of information emerge over time, and each version can be perfectly valid, depending on the use case.

The team that supports an enterprise platform with all these challenges across a global enterprise needs to be as knowledgeable as its user community. That means understanding the technology, the application use cases, data formats and workflows, analytics and displays, and even basic cartography.

Close collaboration between the IT and business organizations helps create the support structure that is critical to achieving enterprise platform success and sustainable results.

Lesson 6: Automation

I cannot stress enough the role that automation plays in a successful geospatial platform deployment. In all my years of working in this field, I have never heard an internal customer say, “Thank you, that’s all I needed.” Everything we touch tends to grow and evolve quickly or spawn a similar effort—all of which leads to more work for the team. This is a great indicator that the team is adding value and the platform is having a positive impact. But without good management, the team can consume all its available resources on new ideas, leaving the core platform to suffer.

To counter that, the BP team created a golden rule early on: If there’s a chance that a workflow will be needed again, automate it the first time. Automation helps on many levels. It ensures consistency and facilitates continuous improvements. It allows more transparent tracking and reporting of process status. Most importantly, it allows a company to run many more processes than could ever be achieved with hands on keyboards. We now run hundreds of automations around the company, with some firing every few seconds and others only a few times a year.

The lesson we learned was to invest as much thought in the automation platform as in the GIS technology itself.

Lesson 7: Marketing matters

When a company deploys an enterprise platform to tens of thousands of employees—whether it’s GIS, ERP, or another technology—branding, marketing, and communications matter. Here are several marketing lessons we learned during our digital transformation:

- Build an identity: To get traction on the big initiatives, create a program brand that users can identify with. We dubbed our GIS platform One Map, which highlighted the theme of a single mapping infrastructure for all of our location intelligence. We then promoted the program identity, rather than the GIS technology behind it.

- Mind your language: At BP, as at any company, executives and professionals tend to think about GIS or ERP as they think about PowerPoint or Word. In other words, applications aren’t particularly important to them; business results are. So, when we began our enterprise platform rollout, we avoided the term GIS in promotional materials. Instead, we spoke to users in language that resonated with them. When we talked to the IT people, we described systems of record, systems of insights, and platforms. When we talked to the business people, we stressed production optimization, safety and efficiency, access to information, advanced analytics and dashboards, and overall quicker time to decisions.

- Communicate: Our One Map launch campaign deployed emails, posters, and flyers in every BP office around the world, as well as advertisements on office televisions, to convey the business benefits of One Map and get BP professionals excited to leverage it. We also created three levels of internal websites. A high-level website conveyed a generic message about location management and analytics and how those tools are used in our company. Another site, titled Community of Practice, was tailored to our technical-savvy data and information professionals. Lastly, a tools dashboard allowed users to dive into specific tools, data models, and workflows in support of specific work. Communication is ongoing and includes regular Yammer posts, news stories, and internal articles. The learning here is to ensure that there is a budget for communication, resources assigned to it, a plan for ongoing engagement, and a concerted effort to end every communication with a call to action.

Lesson 8: Measure success

It can be difficult to measure the impact of something as vast as a location intelligence platform for more than 70,000 employees spread across the world, but it is important to ensure ongoing internal support. One simple way to gauge success is to monitor how many employees become active users of the platform and its apps. At BP, more than 7,000 users signed up to use the GIS platform before we launched our communications campaign, strictly through social channels and other digital sharing. Now, just four months since launch, more than 10,000 users have accessed the system.

Given the diversity of use and the size of the global community, we are now taking our tracking and reporting to new levels of detail, including tracking users, datasets, services, maps, apps, and more on a daily level. These metrics help ensure that we can communicate the impact of the platform, but they also assist in our support of the system. With these details, we can drive better hardware and software decisions, understand which datasets are used more or less than others, as well as see when a technical community is more active in one region than another, signalling that we may need to organize targeted knowledge-share sessions.

Another key way to measure success is by efficiencies gained. If someone at BP can access the data they need without having to load it manually, and users can quickly configure the functionality needed to analyse it, and then decide how to communicate it through maps, apps, or dashboards, we might improve that person’s annual efficiency by 3–5 percent. For a technical worker who needs location intelligence more often, it might be 5–8 percent. Since these gains come from a shared enterprise platform where an app or dashboard can be leveraged in similar workflows, the percentage gain is almost assuredly higher.

When executives add up these productivity gains, factor in the average resource salary and the number of people leveraging the system, and follow progress over time, they can begin to put a number on what a company gains from approaching location intelligence with a geospatial platform over bespoke solutions.

By going to an enterprise platform, sharing information within geographies and across divisions, we have greatly reduced startup time for new analytics projects. Now, more data is available on a platform that's faster to access and use, and, therefore, people can find better insight and drive better decisions.

Brian Boulmay, BP

Our next steps

Digital transformation, whether via GIS, ERP, or another enterprise system, is not the destination. It’s the means to solving business problems by leveraging digital systems and integrated workflows. Given the nature of digital systems, organizations must engage in an ever-evolving effort to update, maintain, and deliver needed capabilities.

Our initial deployments were predominately internally hosted systems, but as we begin to envision the next generation of our platform architecture, we want to move more infrastructure onto the cloud, so our users can access GIS-driven data and apps on any device, anytime, anywhere.

As we have watched the technology evolve, we have also seen the industry’s application of location intelligence change. We believe the number of use cases for location data, analytics, and visualization is about to explode in several areas of our business.

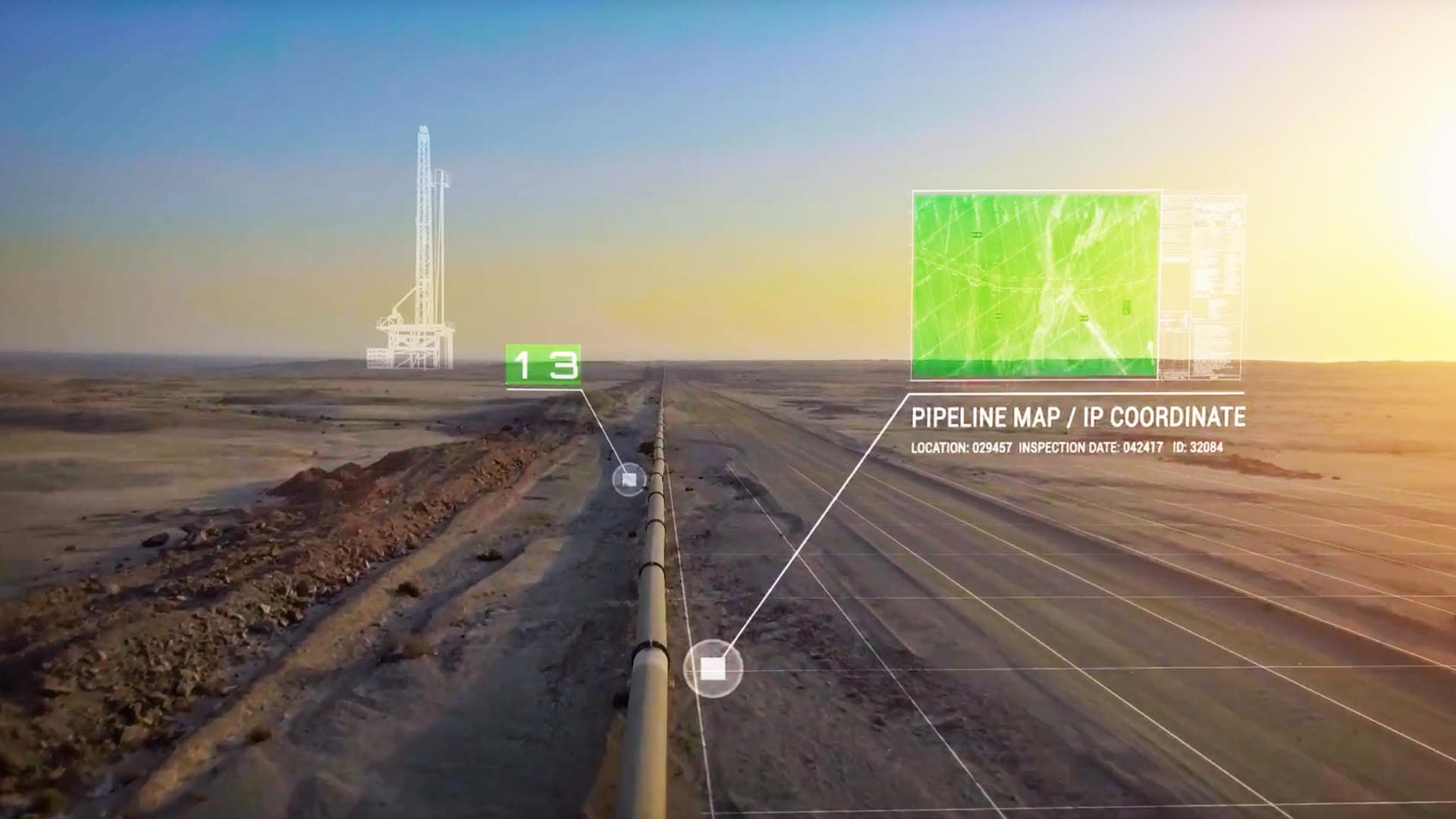

Augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) techniques are beginning to merge with BP’s traditional location-based systems. We are placing sensors on many assets, stationary and mobile, and linking them to real-time Internet of Things (IoT) frameworks. Our building information systems are also beginning to link with real-world geography.

Imagine the efficiency gains we could achieve if an oil field technician could view real-time conditions, whether on a laptop, a tablet, Google Glass, or even an AR/VR display, in the office or the field. In this real-time display, they could view equipment maintenance history, health status, operating parameters, user manuals, or even click a button to kick off a replacement activity—which would integrate with the planning process and send an equipment order to the procurement system. To achieve this, the user needs to be able to track location in the real world, inside the fence line, inside the building, and back again. This will require a level of geospatial awareness, capability, and integration we have not yet seen in our industry.

Many executives might read this and think, “It must have been easy for BP because they had millions of dollars and hundreds of people working on this location intelligence platform.” In reality, we had a very small budget and only five people working to start the platform. We delivered to scale by rethinking some of our traditional approaches to geospatial capabilities. We focused on platform over solution and worked to enable a larger community of users across the business who could drive BP’s data, analytics, and apps forward.

For companies working to achieve sustainable digital transformation in the geospatial domain, the enterprise platform approach is worth exploration. Here at BP, we’ve found that it’s an effective way to distribute the technology throughout the company and multiply its benefits exponentially across our business.

hello: there

Business Advantage through Location Intelligence: The CEO’s Guide

The CEO oversees a company's strategy and operations. This guide reveals how location intelligence benefits those in the corner office.

Editor’s note: This article is the first in a WhereNext series dedicated to CXOs. Location intelligence is a brand of business intelligence that helps executives understand customers and business trends in locations around the globe. Throughout this article, we’ll explain how a CEO can turn location intelligence into business advantage.

A chief executive officer establishes goals for the company and defines a vision for its future. Being responsible for success in a shifting, competitive environment can leave CEOs searching for new tools. One increasingly relevant tool is what Forrester principal analyst James McCormick calls an analytics-driven strategy.

Business leaders “need to embrace insights at scale,” McCormick said on a recent podcast. “We need to have data and analytics technologies that deliver strategic value, not just the typical ROI kind of value. And that value needs to differentiate us. So we need to understand our businesses, our customer, our processes in such a way that it delivers this differentiation.”

Location intelligence can be key to helping a CEO define that differentiation. Location intelligence comes from analysing business data in a geographic context—for instance, the location of sales, the online spending habits of consumers in cities around the world, or regulations and events that affect supply chain decisions.

In short, location intelligence brings clarity to local, national, and global trends. A location intelligence strategy supports many of the CEO’s major responsibilities, including recognising and adjusting to patterns in sales, service, and efficiency across corporate locations, as well as anticipating global market movements and demographic shifts. The engine behind location intelligence is a geographic information system (GIS)—technology that analyses and organises information on smart maps and dashboards.

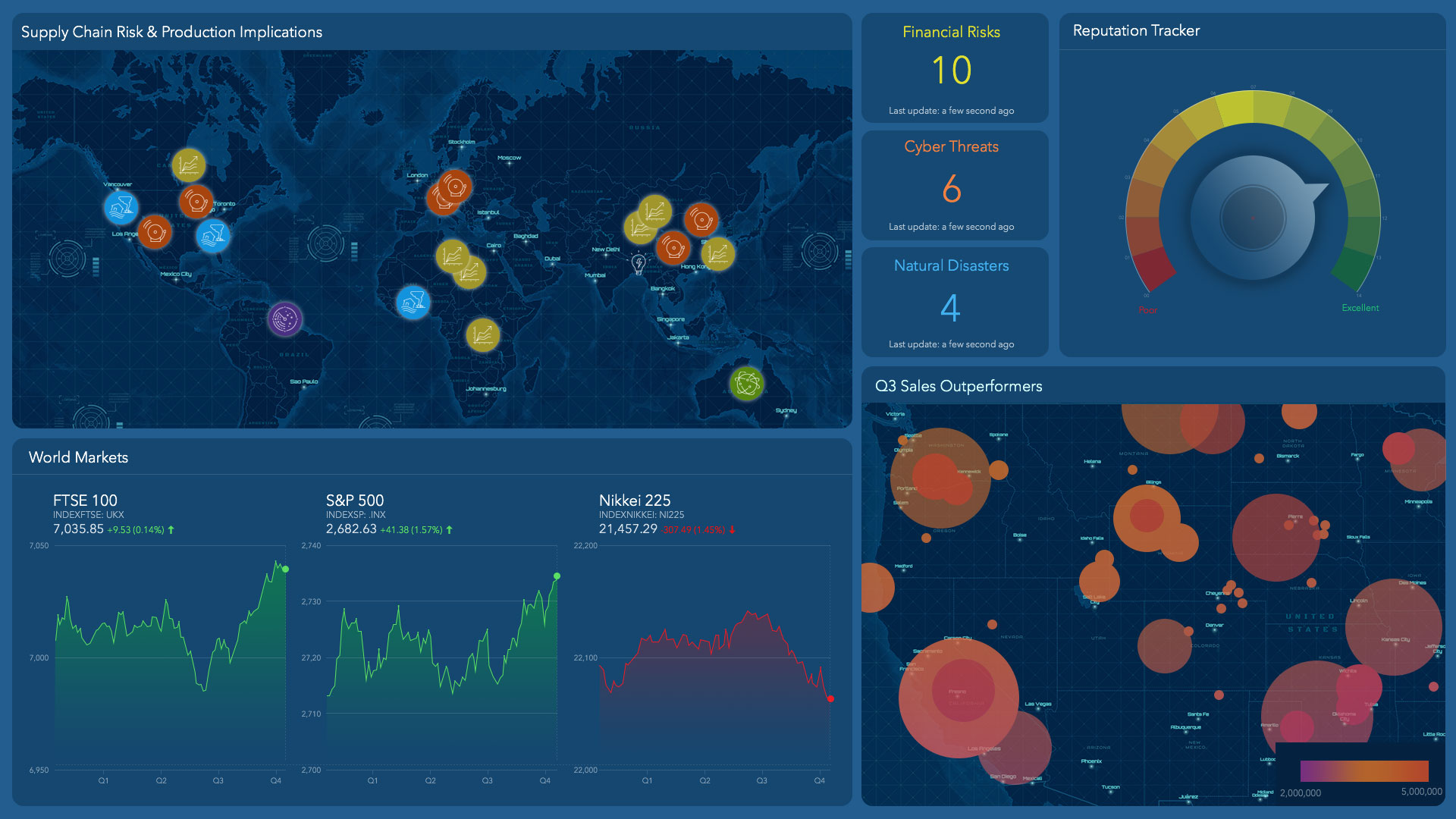

A CEO can monitor the patterns revealed by location intelligence on a GIS dashboard that updates sales trends, customer characteristics, population demographics, supply chain costs and efficiency, and the company’s reputation.

“Peter Drucker, the internationally renowned management consultant, once said the purpose of a business is to create and keep a customer,” says Thomas Horan, dean of the School of Business at the University of Redlands in California. “To serve those customers well, CEOs must have both a strategic as well as a tactical understanding of where the business is in the marketplace and how it is performing.”

In this opening article in WhereNext‘s series on location intelligence for the C-Suite, we explore how location intelligence can support the major responsibilities of a CEO, drawn from real-world situations and case studies.

Monitor and Respond to Business, Economic, and Societal Trends

By analysing millions of data points that affect production, sales, or transportation—from shifting workforce demographics to changing markets and weather patterns—GIS technology distills big data into CEO-level insight. Smart maps provide real-time status reports on trends and conditions that are important to improving current business and planning long-term strategies.

In the manufacturing sector, the trend of declining car ownership provides a useful study in how a CEO might apply location intelligence. Navigating a trend of such significance—with its threat to business models and its board-level visibility—demands reliable intelligence and a well-tuned strategy. A CEO can map out insight from global markets and submarkets to understand how, where, and at what pace consumer preferences for automobiles are changing. With that intel, a business leader can adjust the business model to outpace competition.

Across industries, GIS empowers analysis and action through executive-level dashboards that monitor:

- Trends and risks in locations around the world, providing situational awareness of current and potential markets

- Risk factors or opportunities related to changes in political, cultural, or economic patterns

- Market indicators, including fluctuations in monetary systems, regional or local economies, stock markets, and interest rates in regions around the world

- Social media trending topics that reveal consumers’ concerns about the economy, business, or society

Location intelligence guides competitive decisions by illuminating an area's demographics, including age, gender, education, income, and even nuanced data such as entertainment preferences.

Develop and Sustain a Deep Understanding of the Customer

CEOs must comprehend changing customer expectations and respond with new or modified products and services.

For the founder and president of a large furniture retailer in the Midwest, the early days were driven largely by intuition. But as the business grew—today it ranks among the category’s top retailers in the country—the scale and size of its investments demanded greater rigor. That’s when the CEO turned to GIS-driven location intelligence to understand who and where the company’s customers were.

With GIS data that gave him a deep understanding of not just who his best prospects were, but where they were, the young chief executive piloted an expansion that continues to this day. “Having some additional data to fine-tune [my] instinct was very, very beneficial,” he says.

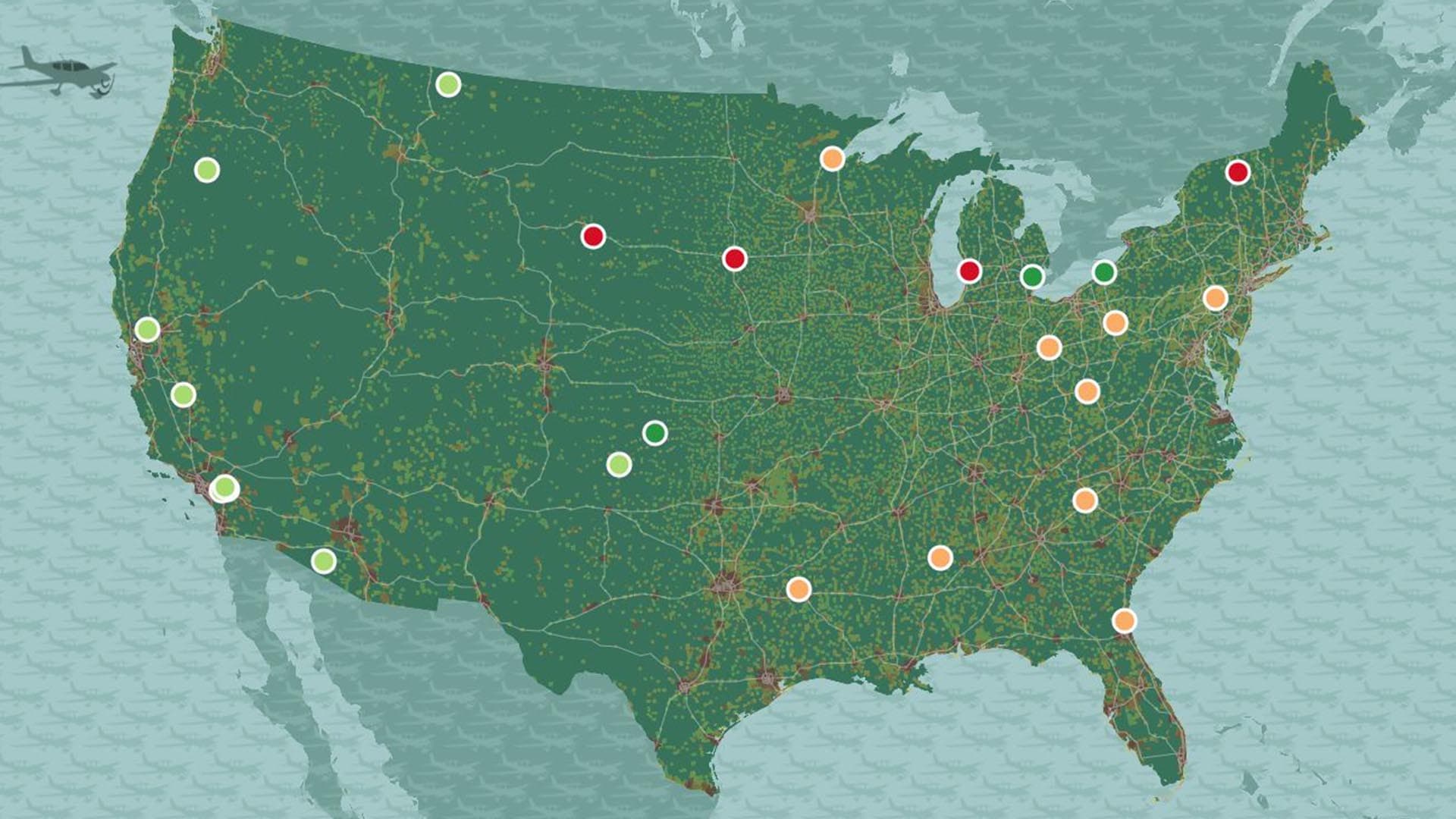

Likewise, when executives at one of the nation’s largest fast-casual restaurants sought to roll out an app that would allow customers to order food on their phones, location intelligence played a key role. For the pilot phase, the company could have simply chosen markets where sales were highest. But the executives dug deeper. Using GIS-powered analytics, they mapped out the cities that showed strong sales and high digital adoption rates. The analysis—which revealed what percentage of people in each city had recently used their phone to make a product purchase—fostered a richer understanding of customers than most executives enjoy. With that insight, the company adopted a data-driven strategy for rolling out its new service, maximising adoption and minimising wasted marketing spend.

Grow the Business and Fend Off Competitive Threats

“A senior executive’s job is to look outbound at the market and pay attention to the competitive stance of the company and its future as a viable entity,” reports Brian Kilcourse, managing partner of RSR Research, in an upcoming podcast.

How Location Intelligence Supports the Roles of the CEO

To establish business goals and set a vision for the company’s future, CEOs must:

- Monitor and Respond to Business, Economic, Societal and Global Trends—GIS can receive real-time metrics and immediately analyse them in terms of corporate strategy, then map them for leadership review.

- Develop and Sustain a Deep Understanding of the Customer—Location intelligence can track and analyse demographic changes, personal interests, and sales for any geographic size.

- Grow the Business and Fend Off Competitive Threats—Get electronic maps of expected population growth, sales, and competitor expansions.

- Decide How and Where to Allocate Resources—Support decisions with knowledge of where likely customers are located and the cost of supply chains that provide products and services.

- Develop and Promote the Best People and Practices—Show the stats and distribution of winning strategies to reinforce success and to underscore which locations need help.

- Ensure that the Workforce Reflects the Diversity of Customer Base—To keep current, make sure your employees represent all the changing demographics and tastes of your customers.

- Protect and Strengthen the Company’s Reputation in the Marketplace—Maintain real-time analysis of social media and public perception of your company to intercede quickly when and where problems arrive with any product or service.

The tricky thing about competition is that it changes. In the utilities industry, for instance, competition was practically non-existent before deregulation efforts in the 1990s. After the dust of that upheaval settled and utility CEOs had recalibrated their market strategies, the ground started shifting again. This time, democratization is the culprit, as individual homeowners, residential collectives, and businesses generate their own power through solar and wind sources. Forward-looking utility CEOs are using location intelligence to understand where that competitive threat exists as well as to plan how to get ahead of it.

In retail, manufacturing, and other industries, intelligent mapping gives business leaders a sense of how specific areas are changing—whether residents or visitors are beginning to skew to an older demographic, display different lifestyle choices, or favour competitor brands. A CEO’s dashboard can track location-based insight such as planned competitor locations and markets where rivals are reshaping product lines.

Some chief executives take a more direct approach, enlisting services that use artificial intelligence (AI) to interpret satellite images and reveal trends among competitors. Others fly drones over rivals’ facilities or fields to understand production levels and techniques. (To learn more about business applications of AI, read this e-book.)

All this data, at local and national levels, feeds into executive decisions about how to allocate corporate resources to expand and develop offerings.

Determine How and Where to Allocate Resources

One large retail chain used location intelligence from GIS to analyse its supply chain and cut its number of service centres by more than half, creating major improvements in customer experience and profitability.

“At one time, the company had almost 50 service depots across the US,” explains Avijit Sarkar, a business professor at the University of Redlands. “They were sending out delivery technicians to service their products at millions of households in an almost haphazard way, because they had not managed this part of the business well.”

With the bottom line suffering from those inefficiencies, the CEO and executive team enlisted GIS—which they had long used to support market development—to help optimize the service and delivery supply chain. They mapped out the locations of customers, technicians, and supplies, and analysed metrics such as:

- Customer delivery and service routes, including time-sensitive deliveries

- Fuel and maintenance costs

- Accident reports and costs per route

- Driver and service personnel salaries and benefits

- Regions of anticipated customer growth

The resultant maps revealed efficiencies that human planners couldn’t possibly have calculated at a national scale. The executive team reduced the number of service depots to 22 from 46, Sarkar says. “Imagine the effect of that. You are servicing the exact same geographies spread all across the US with half the number of offices [and] a significant reduction in truck drivers and fuel costs.”

When CEOs analyse opportunities for business expansion, location intelligence gives them confidence that a new market will support the company's product or service.

Develop and Promote the Best People and Best Practices

In a bustling economy, talent acquisition and retention are CEO-level concerns. To perform reliable long-range workforce planning, a CEO must be alert to hard and soft data about where talent is moving and emerging, and how the company might harness it.

Location intelligence plays a substantial role in that effort. A CEO might map out quantitative data, such as the results from a recent study documenting the migration of millennial professionals to big cities. But just as important is location intelligence drawn from softer data, some of which can signal emerging trends.

James Fallows, longtime contributor to The Atlantic and a former presidential speechwriter, recently published a book highlighting small cities that are driving innovation in America. Reflecting on his travels to those cities, Fallows told WhereNextthat executives should consider seeking talent in unexpected places. As evidence, James cited “a wave of young, technically savvy people wanting to live in, be part of, and help create a real place. Not just to be one more person in the Bay Area scrum, but to be helping to build Fresno or Spokane or Duluth or Greenville or any of these other places.”

Business leaders can use GIS technology to spot those demographic shifts before competitors do.

Location intelligence also helps CEOs pinpoint notable talent and practices within a company. A C-level dashboard might display the locations of the highest rated peer-reviewed employees in a global company, and spotlight product development groups that contribute the most to revenue.

With that location intelligence, an insights-driven CEO can ensure that best practices are captured and continually refinedand that high performers are encouraged, promoted, and retained.

Ensure that the Company Workforce and Culture Reflect the Diversity of the Customer Base

Today’s forward-looking CEO aims to create a workforce that reflects the demographics of the markets the company serves. In this pursuit, productivity is as much a driver as principle. A 2013 study highlighted in the Harvard Business Review found that companies with diverse workforces are 45 percent more likely to report that their market share expanded year over year.

The goal is to foster a culture that draws ideas from a rich group of workers whose outlooks reflect the interests, concerns, and subtleties of the consumer population. The upshot: diverse workforces innovate and perform better than their peers, according to the study’s authors.

To convert this business philosophy into practice, an executive team can create user personas that embody the traits of key customers. GIS technology has guided that process for decades. “Bethany” might be a working mom with high disposable income, high expectations for customer service, and loyalty to brands with sustainability programs. “Tyler” could be a young minority working in the financial services industry, with a keen awareness of changeable trends in pop culture. Smart mapping can reveal where those and other key groups work, live, and play.

A CEO can make sure the company’s workforce and product mix represent those key customers as well as future ones.

Protect and Strengthen the Company’s Reputation in the Marketplace

A company’s reputation can crash overnight upon the news of a customer data breach or an executive’s inappropriate behaviour. Recent inductees to this dubious club include Theranos and Cambridge Analytica.

Data-Driven Leaders

At the heart of a data-driven strategy is an effective digital transformation program. To learn how standout companies have approached digital transformation, visit this e-book.

For most companies, though, reputation ebbs and flows in much subtler ways, across channels almost too numerous to count. Consider the impact one Tweet can have, coming from someone with significant influence. Then consider the breadth and complexity of all the Tweets directed toward a company. Nike, for instance, was mentioned 2.7 million times over two calendar days in September 2018. And those are just Tweets.

Peter Buell Hirsch, global consulting partner and reputation and risk lead at Ogilvy, touts the role of “influencer maps” in helping executives understand where notions about a company or industry originate. A combination of GIS technology and sentiment analysis can create these maps, sifting through millions of real-time indicators to reveal signals worthy of a CEO’s attention.

The location-aware CEO can use GIS to track other markers of influence too—anything from sales in specific markets to regional net promoter scores (NPS) to feedback from frontline sales and service employees.

If low scores crop up in certain locations, executives can analyse whether the discrepancy relates to the company’s professionals, its customers, or both. Pinpointing the cause helps prevent the problem from developing elsewhere. In this way, location-based insight helps a company improve products and services and enhance its reputation as a responsive and forward-looking enterprise.

Create a Location-Aware Enterprise

Jeff Bezos, who has led Amazon since he founded the company in 1994, said in a 2017 interview that his job as CEO is to make a few big decisions each day. For any chief executive aspiring to Amazon-esque success, the advice is instructive. But it’s also incomplete.

After all, making a few significant decisions each day is possible only when good intuition meets good data. And finding good data—strengthened by location intelligence—takes a focused effort by the CEO and executive team. In the words of business school dean Horan, “CEOs should create a culture that makes location intelligence a trusted resource in the C-suite.”

The above guide offers a framework for how CEOs might apply that insight. They would be well-served to act soon. In 2018, Forrester’s McCormick says, most companies can survive without an insights-driven strategy, but that won’t be true for long.

“You can still work, you can still compete, you can still exist,” he explains. “But you’re rapidly losing market share, or you’re certainly losing your competitiveness in the market. And there will be a time between now and . . . around 2021 where if you don’t have A) an insights-driven strategy, and B) if you’re not somewhere down the road, you would have lost the race already.”

A Media and Publishing Company Delivers Location Intelligence to Advertisers

The Star Tribune offers prospective advertisers GIS-based consultations on how to find customers and grow their business.

While the newspaper industry shifts its strategies to meet the challenges of an ever-changing digital age, one well-respected media company has found an innovative way to turn prospective customers into loyal advertising partners.

The Star Tribune Media Company in Minneapolis has created a twist on the traditional newspaper-advertiser relationship. Instead of simply selling ad space in its print and digital channels, the Star Tribune consults prospective advertisers on market development, including how they might grow their business.

Using sophisticated geographic information system (GIS) technology, the Star Tribune delivers this high-value location intelligence without charge and without a customer commitment. The same work by an outside consultant could cost tens of thousands of dollars.

Why is the Star Tribune willing to offer so much to attract a potential customer? In large part, because the location-based analysis it produces is the quickest way to show prospects the value of partnering with the Star Tribune.

Swimming against the Industry Tide

The Star Tribune’s approach to sales has helped attract and retain customers during a difficult period for the publishing world. In a 2017 report, the Pew Research Centre found that with few exceptions, newspapers faced declining revenue during the past several years, and that total weekday circulation for US daily newspapers (counting print and digital) dropped 8 percent in 2016.

The Star Tribune has been abler than most to swim against this industry tide by keeping print products strong, developing digital platforms for news, and serving as a partner and consultant to advertisers.

While many companies promise to partner with customers after the sale, the Star Tribune often delivers vital location intelligence—at no cost—even before an advertising contract is signed.

“We don’t have any hesitation about that,” says Steve Yaeger, vice president and chief marketing officer for the Star Tribune. “Because the type of analysis that we do will open up all kinds of other insights about your business, and it will lead you to make a decision for the Star Tribune.”

Knowing Where and How to Develop Markets

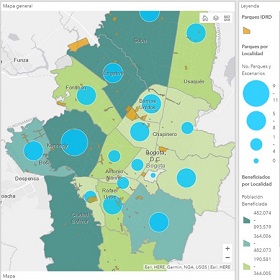

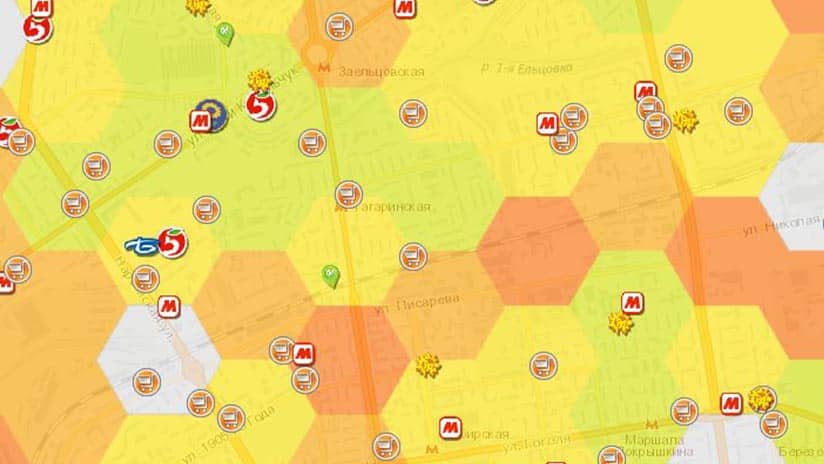

The Star Tribune’s complimentary, GIS-powered analysis focuses on market development. It tells an organization the location and interests of customers and identifies which advertising channels are likely to be most effective. This location intelligence gives a prospective advertiser confidence in the Star Tribune’s solutions and, in turn, helps the Star Tribune hit the ground running if the company decides to advertise.

This approach has led to a growing group of clients that range from single-location, higher-end merchandisers and organizations to companies with revenue in the billions. All have enough trust in both the GIS results and the Star Tribune to do something that’s rarely seen in the business world: they share their transactional customer database for analysis by the Star Tribune’s marketing department GIS team.

The media company signs privacy and nondisclosure agreements with businesses that share such data. Yaeger takes pains to note that while the newsroom uses GIS to conduct research and create maps for news stories, the marketing department’s GIS team is completely separate.

Sometimes [an advertiser] might be over-saturating an area that's not producing for [them], and it's not at all uncommon for us to tell an advertiser to reduce their spend in a given geography.

Steve Yaeger, Star

Tribune CMO

A History of Customer Partnership

Some business analysts caution against using free consultations because they can be worthless gestures or, at the other extreme, profit-killing giveaways of valuable products or services. But the Star Tribune has struck a unique balance.

Wayne Johansen, founder of the $250 million HOM Furniture, was the first customer to use the Star Tribune’s market development guidance. He credits mapping and demographic analysis for supporting his company’s fast rise and says HOM Furniture has maintained its success through ongoing market analysis.

Of his early days in the business, Johansen says: “We were in a fast-growth stage and we felt that we had a winning game plan. But the execution became much more scientific and precise with the tools and analysis we were able to get from the Star Tribune.” Johansen’s company recently was ranked eighth among the top 50 regional furniture chains.

Based on the experience with HOM Furniture and other early clients, the newspaper took the unusual step of creating its own GIS Customer Analytics Department with a director and two full-time GIS analysts.

Carlos Ruiz, the director, says many prospective advertisers struggle to understand who and where their best customers are.

“The No. 1 question we try to answer is: Where are your customers coming from? And that seems like a simple question. Most advertisers with physical store locations have a gut feeling of where their customers are located and how far they will drive.”

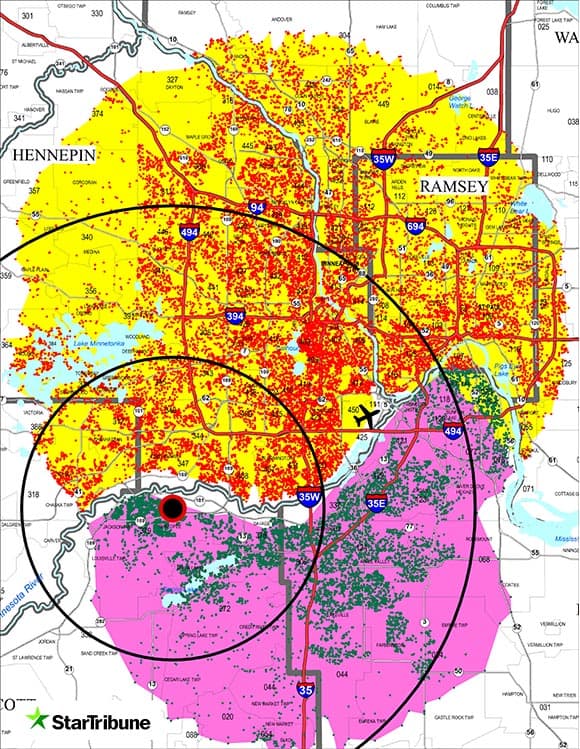

But when Ruiz and his colleagues analyse a company’s database and plot its customers’ locations on a GIS-powered map, the business owners often are surprised. “More often than not, the mean centre of the customers’ spatial distribution is a mile, or three miles, or even five miles away from the store location.” (See the image at right for an example.)

Once the advertiser sees that high-level location intelligence, Ruiz explains how deeper analysis can sift out customer traits—their locations, interests, age, gender, and purchase history with the business. (See the sidebar, “The Science behind the Insight.”) That step is key to successful market development, since it helps reveal the best way to reach the people who are likely to become customers.

Planning Ad Campaigns Based on Location Intelligence

Even successful organizations with deep local roots can find the research eye-opening. In one case, a well-regarded arts organization was certain that its main event location was the geographic centre of its customer base, and that some members would not drive across the Minneapolis Saint Paul region to attend events there.

But the Star Tribune’s analysis of the group’s transactional database showed that customers were much more spread out and willing to drive long distances. When the GIS analysts added to the customer distribution map several layers of demographic traits such as age, income, home ownership rates, shopping and travel preferences, and other personal interests, they found previously undiscovered patterns.

By analysing their actual transactional databases, we can help our advertisers to make sound marketing decisions based on actual facts instead of just intuition.

Carlos Ruiz, Director, Star Tribune Customer Analytics

“We can tell an advertiser that X percent of your business is coming from customers who look like this,” Yaeger says. “They’re living in these locations. . . . If you could reach more people who look like this or who live in these areas, then chances are you would do well with them.”

After digesting the surprising GIS findings, the group re-examined its strategies for reaching out through a variety of print, online, direct mail, and digital products offered by the Star Tribune that they had previously underutilized.

Matching Customer Segments to Digital and Print Ad Campaigns

The Science behind the Insight

Purveyors of GIS technology have taken a scientific approach to understanding consumers. Decades of research, for instance, have shown that customers who share particular characteristics tend to exhibit similar purchasing habits. GIS technology identifies where certain groups of those consumers live and where they might shop. For more, see, “The Enterprise Technology behind Big Business Decisions.”

The Star Tribune is proud of the fact that although Minneapolis Saint Paul is the sixteenth largest metro area in the country, the newspaper has managed to rank fifth in the nation in Sunday print circulation.

Meanwhile, the Star Tribune takes its own advice, examining its database to figure who its core customers are, and where to find more of them. Recently, that GIS research indicated support for adding two other print options (a weekly household-requested free newspaper that’s an abridged version of the daily newspaper, and an advertiser supported “shopper” product). With that, the paper’s print products now reach 1 million unduplicated households—a plus for readers and advertisers. The company’s expanding digital products draw 8 million unique visits each month.

As business leaders know well, a digital strategy is a key part of market development. Using customer demographic information, interests, and purchasing history, Star Tribune advertisers can aim digital ads toward certain types of people who read the newspaper online. The newspaper’s revenue from digital services was about 5 percent of its revenue in 2013 and 10 percent in 2016, and is on track to hit 15 percent by 2020.

The Star Tribune’s GIS mapping helped us pick new store locations, forecast sales, and in one case, it showed us that we should go ahead and close a smaller location and open up a larger one elsewhere.

Wayne Johansen, HOM Furniture

Location Intelligence and Business Instincts Guide Market Development

Johansen of HOM Furniture is something of an instinctual businessman—one who had the savvy to recognize a Midwestern market ripe for his retail furniture stores. He even picked some of the first locations himself. But Johansen also realized he needed new technologies to support the growth he envisioned.

In one of the first analyses Johansen received from the Star Tribune, Ruiz overlaid demographic data on a map of HOM’s customer distribution, revealing in precise detail how location, income, age, family size, and lifestyle interests related to the types of furniture that customers were buying at different HOM stores. “We were surprised by how concentrated some of our business was in some [customer] segments,” Johansen says.

Ruiz helped the company figure out how to identify store locations that would reach new customers without losing current ones. Location intelligence also worked on subtler levels, leading Johansen to maximize sales by stocking different items at different outlets—all based on the predicted buying patterns of people likely to patronize each location.

As HOM Furniture grew, its advertising grew as well. The company increased its purchase of multipage, colourful inserts from about 10 annually to more than 40 a year. HOM also added new Star Tribune advertising products from direct mail to digital outreach, as the location intelligence supported those strategies.

“What was happening was that they were lifting our boat and we were lifting theirs at the same time,” Johansen says. “The Star Tribune’s GIS mapping helped us pick new store locations, forecast sales, and in one case, it showed us that we should go ahead and close a smaller location and open up a larger one elsewhere to more efficiently serve that area.”

Insight for Inventory Adjustments

Later, as competition and profit margins tightened, HOM Furniture’s partnership with the Star Tribune paid a new kind of dividend. Johansen found that his company could profit not only from expansion, but also from adjusting marketing activities based on the locations of customers and competitive specialty stores. “The Star Tribune helped us find certain categories like mattresses and break out some of those numbers to identify places where there’s not as much competition for those products,” Johansen explains.

Even if more mattress stores later moved close by, pushing HOM to decrease its emphasis on the product in those areas, the Star Tribune still helped them uncover a profitable vein that they might not have seen as quickly, or at all.

Ruiz and Yaeger are pleased with the long-term relationships that have flourished since the first round of free consultation with HOM Furniture years ago. That initial partnership formed the Star Tribune’s template for helping prospective clients develop their markets based on location intelligence.

“We want to [do] more than just sell advertising,” Ruiz says of the Star Tribune’s approach. “We want to become partners with our advertisers.”

Finding AI Talent Using Location Intelligence

HR executives can leverage location data to identify and attract top AI candidates, despite limited supply.

Job postings for artificial intelligence (AI)-related roles nearly doubled in the US between 2015 and 2018, while searches for those roles increased 182 percent, according to job website Indeed.com. New York and Silicon Valley headlined the list of regions with the most AI-related jobs, with major cities from coast to coast rounding out the top 10.

AI’s job growth rate illustrates its expanding role in business. Joseph Sirosh, corporate vice president of AI at Microsoft, said in a recent podcast that most large-scale work will eventually be powered at least in part by artificial intelligence.

“Every type of customer support will be AI-infused,” Sirosh predicted, adding that companies will use AI “to understand their customers, manage their supply chain, set optimal pricing, and create great experiences.”

As the Indeed study underscores, companies that haven’t yet invested in AI and machine learning might consider whether their competitors already have.

(For a glimpse of how leading businesses are using AI to their advantage, visit this eBook.)

Recruitment Strategies for AI Roles

In an economy marked by labour shortages, the field of AI is no exception. In its report, Indeed observed that a significant percentage of jobs remained unfilled for 60 or more days.

“Skills to build AI capabilities […] are still in short supply,” Sirosh said in his interview. “That profession will blossom. Every computing department, every computer science department teaches AI as a fundamental course now. So, it will change. It just takes a little time.”

In the meantime, businesses that hope to compete for today’s limited AI talent could benefit from location intelligence—drawn from the data in Indeed’s AI report and other sources.

Since AI is an emerging field, many professionals with the skills to apply AI in business are recent college graduates. Different types of graduates fill distinct roles in the emerging AI space, so companies must clearly define their AI strategy before crafting a talent recruitment plan.

For instance, companies focused on customer service may need graduates with natural language processing skills to build chatbots and other AI-driven customer experiences. Others could seek professionals who can build AI models to forecast retail markets. Knowing where to find candidates is the next step.

An HR executive might first identify key skill sets that will advance the company’s AI goals, then map the schools and geographic areas with recent graduates who have complementary AI skills.

After assessing the AI landscape and locating promising talent centres, executives can launch targeted recruiting programs. A program might focus on drawing talent to the company’s existing locations, staffing satellite offices in areas of talent concentration, or both.

To draw high-value AI talent to the company’s existing offices, executives might undertake initiatives to make their headquarters more attractive to Millennials and Generation Z recruits. Companies could also partner with local economic development agencies to enhance and market their city’s appeal.

An alternative is to take the office to the talent. Some companies have chosen to establish satellite offices or centres of excellence near hotbeds of AI and machine learning. Pittsburgh is a recent example of this phenomenon. Companies like Uber, Ford, and Delphi flocked to the city in recent years, hoping to snag alumni from Carnegie Mellon and the University of Pittsburgh who could fuel their autonomous driving efforts.

Choosing the right neighbourhood for a headquarters or satellite office can make or break a company’s ability to attract talent. Location intelligence, powered by a geographic information system (GIS), reveals the demographics of neighbourhoods, ensuring that a company can situate itself in an area attractive to young AI grads.

One of the selling points of artificial intelligence and machine learning is their growing ability to help business executives make better decisions, faster.

Future Focus for AI Jobs

Companies that don’t plan to add their own AI team will still need an AI strategy to stay competitive in years to come. Some might consider outsourcing to compensate for the limited talent supply reported by Indeed.

The first step, however, is to identify the specific business opportunities AI and machine learning would address. Then, executives can work on finding appropriate talent or a service provider.

Taking a challenge-first approach and analysing all available data, including location intelligence, will illuminate the type of candidates who should fill new AI roles, where those candidates are, and how a company might attract them.

Photo courtesy of Andre Hunter.

This article was originally published in the global edition of WhereNext.

Think Tank: Defining the Business Case for Drones

The companies using drones to their greatest potential understand the strategic value of location intelligence, experts say.

Drones have flown into public discourse powered by quad motors and hobbyist appeal. They hover over landmarks, snapping pictures for photography enthusiasts. They form airborne networks to create modern-day fireworks displays.

But what are drones doing for business? How will that evolve in the next several years? And, how have drones improved with the help of big data, IoT, and artificial intelligence?

WhereNext assembled several thought leaders to explore these questions. In this latest instalment of the Think Tank series, Esri Professional Services VP Brian Cross leads a discussion with Don Carson, an expert on location intelligence for the utilities industry, and Mansour Raad, a specialist in big data, artificial intelligence, and location intelligence across industries.

Defining Business Value

Brian Cross: I want to cut through the fluff about drones in business, and find out what you’re seeing in reality and on the cutting edge. Don, in your experience, where are executives seeing real business value in unmanned aircraft and remote-sensing capabilities?

Don Carson: There are really two key areas of business value today. One is gaining efficiencies and reducing operating costs, and the second is employee safety. Drones can take video or photographs to assess conditions and help companies pinpoint where services or equipment might be at risk.

A recent report [by Skyward, a Verizon subsidiary and maker of drone software] showed that while only 1 in 10 companies use drones today, 88 percent of those that do have achieved a positive return on investment within a year.

Competitive Advantage and IoT

Industry leaders are outpacing competitors by combining IoT data with machine learning, predictive and prescriptive analytics, and location intelligence. Learn how in this eBook.

The companies we work with are taking advantage of drones to get into the field faster, cheaper, and with greater safety.

Mansour Raad: Another way to look at it is that drones extend the human senses. Today, companies are using drones to help employees see situations from new vantage points. Tomorrow, drones will extend our other senses, including hearing for noise detection around airports, perhaps; and smell for detecting gas leaks, for example.

The Drone Playbook

Cross: What are some of the workflows and business problems drones are addressing now?

Carson: One example is inspections for utilities—of poles, wireless towers, wind turbines, and other infrastructure. Traditionally, those have required a great deal of time to perform, and come with a high risk to employee safety. In fact, tower climbing is recognized as among the most dangerous jobs. And a single tower climb can cost between $2,000 and $5,000. Drones make that work faster, cheaper, and safer.

Cross: But there’s more to using a drone for business purposes than a hobbyist might realize.

Carson: That’s true. Companies that see the best return on this technology have what we call a high location IQ. They understand that you don’t just launch a drone and hope to find something that benefits your operations. They identify a business challenge, define the flight paths that will help them assess the challenge, and then use location intelligence to analyse the data and identify actions they should take.

Since drones can fly quite low and deliver high-resolution output, some agricultural companies are using them to detect crop health—down to individual plants and individual leaves.

Don Carson, Esri

Extending the Human CPU

Cross: Mansour, how are companies making sense of the big data collected by drones, and how are they doing that more efficiently than the human CPU can?

Raad: Actually, the technology for processing and analysis is starting to become fairly attainable to everybody, and a lot of organizations already have the infrastructure to support it in the form of data lakes and streaming data processing.

At this point, most companies that use drones are in batch mode. They fly the drones, take pictures or video, then download the data into their data lakes on premises or in the cloud. Some advanced companies are streaming drone footage in real time. More companies will be doing that before long. [See the sidebar, “IoT, Edge Processing Transform Drones.”]

To break through the limits of the human CPU, as you call it, smart companies are using artificial intelligence and machine learning to process drone footage. At the beginning, a human employee labels some of the images—identifying a broken insulator or a leaky valve, for instance. The AI program learns from that and takes over the analysis.

To visualize that analysis, most companies use a geographic information system [GIS], which delivers location intelligence in the form of beautiful, expressive maps. They use the maps to pinpoint where field crews need to take action, such as replacing a faulty insulator or repairing a leak.

Precision from the Air

Cross: We talked about the telecom and utility scenarios. Where else do you see companies putting drones to work?

Carson: Agriculture is an interesting use case. Since drones can fly quite low and deliver high-resolution, multispectral output, some agricultural companies and farms are using them to detect crop health—down to individual plants and individual leaves.

An agricultural expert looks at the raw footage, identifies a set of affected leaves, and then artificial intelligence does the rest of the analysis by learning what indicates poor crop health. The analysis is mapped by a GIS which identifies the location and condition of specific plants. In the end, the farmer learns precisely where crops are doing well and where they’re doing poorly, and can adjust treatment with precision. That’s having a big impact on crop yield and the bottom line. When you consider that just one crop disease in one state cost the industry $104 million in a year, you get a sense for why detection is so important.

Raad: And agriculture is an area where drones might provide more than visual inspection. When most people think about imagery, they think about what they see when they look at their house in Google Maps. But remote sensing has long been able to take advantage of other data to do things like sense crop moisture. Drones are adding that type of analysis to their capabilities.

Eyes on Business Expansion

Cross: Don, what are you seeing in terms of drones helping companies manage the growth of their business and infrastructure?

Carson: As companies expand, they’re constructing new facilities, and they’re using drone technology to support expansion. During construction activities, drones can:

- provide status reports on progress

- perform volumetric calculations to show when building materials are running low and need to be restocked

- and reveal potential risk areas on a construction site

There’s a high degree of human involvement in site inspections, so drone-based surveys typically save money and time.

Another use for drones isn’t in the sky at all. Some organizations are using ground-based and indoor drones to map their facilities. Drones take pictures or lidar images throughout the facilities, and then GIS technology creates maps and floor plans that give employees a common view of the workplace or industrial environment. By combining those maps with data from IoT devices like smartphones or sensors, companies can do advanced routing and analytics on the indoor environment, including patterns of movement, assets, and infrastructure. It’s a whole new frontier for companies in many industries.

Today, drones are primarily extending our vision. It will be very interesting to watch as they evolve to encompass our other sensors, such as noise, aura, and smell.

Mansour Raad, Esri

Assessing Asset Health

Cross: Mansour, are you seeing other uses for drones overseas?

Raad: We are. In one case in South America, a natural resources company is analyzing drone imagery to extract hidden features such as roads. They use artificial intelligence to infer where the roads are, and that helps them create an accurate map of their network and route supplies more efficiently.

In northern Europe, a timber company is using drones and AI to manage resources. They want to see which trees are growing where, and how healthy they are. So they’re using drones and GIS to identify where particular trees are, what kind they are, and—more importantly, based on a combination of photography and lidar data—understand their growth over time.

Drones for Competitive Intelligence

Cross: Historically, some large companies and hedge funds have used satellite imagery to gather intelligence on competitors—noting the status of a new facility, or how much oil a company has in its reserves. Are drones making it easier to gain competitive intelligence?

IoT, Edge Processing Transform Drones

Drone footage processing has already begun to move from batch mode to real time, thanks to powerful edge processing and faster IoT communications.

As that data streams in, GIS technology creates maps that indicate where a company should focus its resources. That might help an insurer dispatch adjusters more efficiently after a storm, or allow an agricultural company to pinpoint crops that need targeted treatment.

“With these new IoT and edge capabilities, companies can get immediate feedback on their assets and reduce time to resolution,” explains Mansour Raad, an AI expert at Esri.

Carson: Yes, certain companies are “spying” on competitors by flying drones above their facilities. The simplistic example is a retailer that flies a drone above a rival store and uses the number of cars in the parking lot to estimate sales. That costs a lot of money to do with satellites, but with drones it’s more manageable.

Another case we’ve seen is wineries. Drones can fly over competing wineries to examine growing conditions, slope, and planting patterns. That kind of location intelligence can be valuable to business executives.

More than Eyes in the Sky

Cross: Where do we go next with drones? Are there any scenarios where the drone won’t simply be eyes in the sky, but will perform a business task?

Carson: Telecom companies are exploring drones as a way to cover gaps in wireless cell coverage. Think of the drone as an airborne cell tower and antenna all in one. This could be especially useful during hurricanes and other natural disasters—providing temporary wireless communications to first responders, for instance.

Raad: Facebook and Google are already experimenting with similar techniques to provide Wi-Fi in developing countries. Facebook has developed solar drones that stay aloft and provide service—although they may outsource that work. Google’s Project Loon—which is now its own company under the Alphabet umbrella—uses balloons to provide wireless connectivity.

Amazon hasn’t been shy about wanting to deliver packages by drone, and some logistics providers are planning their own fleets of drones for last-mile deliveries.

Perfecting all these applications will require a high location IQ, because you can’t get the right products to the right people without reliable location intelligence.

Growth Insights: Getting Ahead of the Country’s Changes

Authors James and Deborah Fallows share insight on how America is changing, and how cities outside the mainstream are playing a vital role.

People and places are changing. Business executives looking for signals of what’s to come in the next decade may be intrigued by the perspective of James and Deborah Fallows.

Over the course of five years, the married writing duo explored the United States one small city at a time. They turned their observations into the bestselling book, Our Towns.

The Fallowses recently sat down with WhereNext to share some of what they learned. While both are quick to note that they are not business analysts, the trends they observed are worth noting for business executives.

Contrary to the narrative that all top young minds are flocking to big cities, the couple found talent and passion abundant in the nation’s smaller urban areas. Their observations hint at a country whose economic centre may become noticeably more diffuse.

Sensing Trends in Location, Talent

WhereNext: You spent time as a speechwriter [for President Jimmy Carter]. If you were making a speech to a business executive about what you learned from your travels, what would you say?

James Fallows: I would say that there’s a historic wave they want to get ahead of rather than behind—a wave of young, technically-savvy people wanting to live in, be part of, and help create a real place. Not just to be one more person in the Bay Area scrum, but to be helping to build Fresno or Spokane or Duluth or Greenville or any of these other places.

Not everybody will be interested in doing that, but a lot of people will. The real estate advantage is there. The connections are there. There’s a pool of talent looking for places [where] they can be involved and have a different kind of life, and there are all these local opportunities in things like agricultural technology in the middle half of the country, and places with a manufacturing heritage.

The combination of several trends makes this a uniquely advantageous time to look into the rest of the country for locations. Partly, there is a negative force: simply the cost of working in the biggest cities. The cost of real estate in half a dozen cities in the US is crippling and it sort of destroys everything else in your life or business. In the rest of the country, the cost of real estate is much less. It just means you have a head start. You kind of start out going downhill in your business operations.

The Early Stages of the Business Cycle

WhereNext: The business cycle tends to start with an individual and a dream. But as small businesses grow, big businesses take notice and make acquisitions—as with craft breweries, for instance. Did you see the early stages of that cycle in some of the locations you visited?

Deborah Fallows: I was struck in many of these towns where, [for families] opening the craft brewery, the intention was to make a viable business for them and their young family so that they could stay in Duluth or Fresno or Winters, California. Actually, [these business owners] seemed to have a very slow and conservative approach toward their goals. The end of the dream was not to build a giant brewery and be acquired. The end of the dream was perhaps to have a couple breweries in the town, or to expand and grow the one they have.

This was part of their bigger picture: being in a community where they could raise their kids and create a balance between their work and family and civic activities.

With deliberate, slow growth, they could maintain a balanced life and not get into a place where they either risked their business or risked their lifestyle. A small-town, successful enterprise could integrate into the town.

Compared with the days when we were growing up, it seems like there are so many more small businesses starting around local products and themes. Young people are often taking the lead.

Deborah Fallows

The brewery in Duluth is really a good example of that: two young couples, who now have little kids who are elementary school age, starting the Bent Paddle Brewery. They talked a lot about being part of that community and being in a position to have the kind of leadership to make the schools strong, make the recreation fun, make it a nice place for kids and families to grow up. But they didn’t talk about, “We’re going to make this brewery into a fantastic place and sell out to Pabst Blue Ribbon,” or whatever that might be.

Fostering New Business Growth

WhereNext: How does a particular location foster business growth? Where did you see that playing out?

Deborah and James Fallows discuss their travels at a recent conference.

James Fallows: I think you’re probably aware, from the Kauffman Foundation report, that all of the net job growth in the US economy is from businesses in their first five years of life. So what matters for having a growing job base is new businesses.

I’m thinking of places where we saw new manufacturing bases—Louisville and Erie and Duluth and Wichita and also Mississippi. There was a deliberate fostering environment. There were community colleges and universities where they had extension programs, and some community financing networks in Duluth.

We saw a lot of cooperative efforts that succeeded. In Duluth, with its furniture manufacturing and kitchen utensil and aircraft-component manufacturing, and then the huge aircraft works, all these were results of deliberate fostering efforts.

WhereNext: Were there other specific efforts that stood out to you?

James Fallows: In Wichita, there was 1 Million Cups. It’s a network to get people connected, and get them going. Again, this sounds obvious, but standard economic theory assumes everybody is working just on his or her own, independently. Political rhetoric usually assumes that, too. So, simply the idea that success requires these informal networks was impressive, and every place we saw that succeeded, they had those.

There's this resurgence of locally conscious, walkable, downtown-based enterprises that we saw.

James Fallows

One other point is that in a lot of these [smaller] cities–it’s not that they were doing special favours for a business, but they are in the mood to get things done as opposed to not get things done. Of course, there are city governments where that is not the case—for example, if you lived in Washington, DC, or in San Francisco. But Columbus, Ohio, is very notable [for] just saying, “Okay. We are the scale where we can make things happen. If you have a problem, we know how to make it fixed.”

Finding the In-Between Places

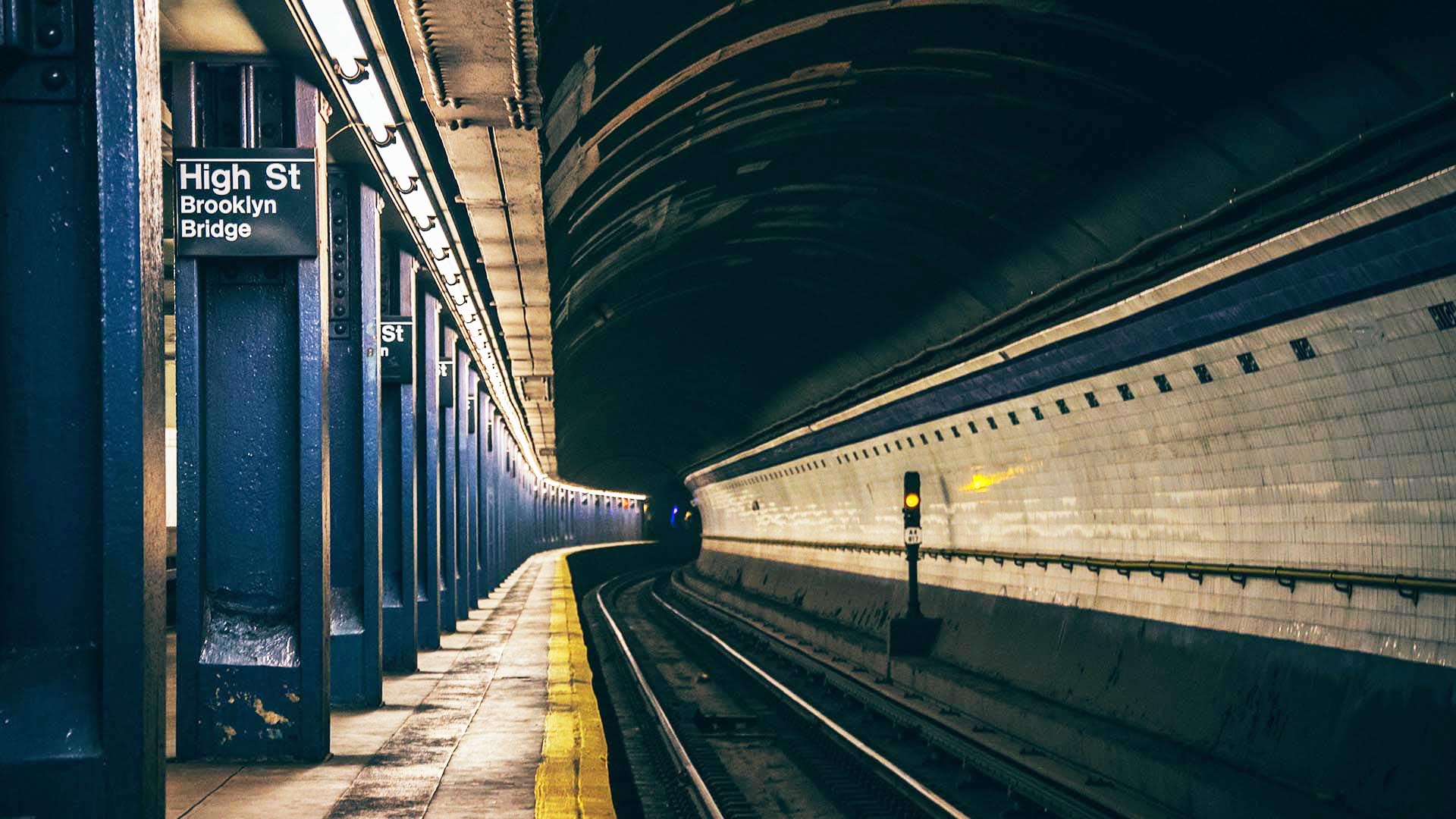

In planning their journey across the United States, James and Deborah Fallows used a geographic information system (GIS) to map out smaller cities with similar economic challenges.

“GIS was an important part of our understanding where we were going and trying to envision” the economic realities of those locations, says James Fallows. The location intelligence delivered by GIS helped steer the authors toward places outside top-tier cities, where they could observe burgeoning businesses and a set of priorities different from those of people in major cities.

Deborah Fallows: And the network within a small town [is important]. The old cliché is it takes a village to raise a child. [This] seemed to be the case of “It takes a village to start this business here or make sure that it is nurtured,” that we saw in towns that were as big as Columbus, Ohio, where the city government has a small business concierge to help all the young entrepreneurs with food trucks, for example, navigate the laws and the rules so that they had a much better chance of succeeding than not.

The Characteristics of Success

WhereNext: A lot of cities have hard-luck stories, and a lot of cities have good, accomplished, smart people trying to turn them into better stories. But they don’t all succeed. Did you see anything notable in the people who managed to succeed?