Blog Archives

How Companies Are Planning for a Wave of Senior Living

Businesses use location tech to anticipate new markets as aging populations alter economies, lifestyles, and housing needs around the world.

A seismic population shift portends immense economic change across the globe, and the most forward-thinking business executives are searching for ways to position their companies ahead of these changes.

By 2030, one in five people in the U.S., 20 percent of the nation, will be over age 65. Globally, the trend is similar.

The so-called silver wave will influence many parts of the economy. Retailers and service providers will seek out seniors residing in age-defined communities that create clusters of older consumers in one location. Housing providers will be testing the market to gauge demand for independent living, assisted living, and skilled nursing care.

Many other options also are being developed for those who want to age in place at their current residence, and those who want something in-between, such as smaller apartments with shared living, kitchen, or recreation facilities.

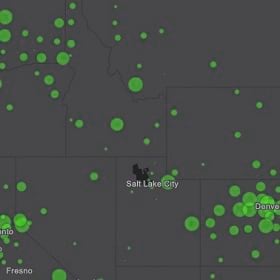

As this complex market grows, some businesses already have turned to geographic information systems (GIS) to predict where growth of older populations will be concentrated and which economic choices and personal interests those residents will pursue. With sophisticated location analysis, GIS software can forecast patterns of migration, consumer behaviour, and housing preferences, including who is likely to move and where.

Article Snapshot:

Developers and consultants hoping to cater to seniors with a high level of home equity are using predictive tools to anticipate where they will live and what kind of housing they’ll expect.

Choices Grow for Senior Living Options

The larger the over-60 segment grows, the more varied its interests and needs will be—and the more informed a business must be to win those customers.

While many seniors may choose to live near their adult children or stay in the area where they raised families, many others are willing to relocate to find the community and climate they want. Knight Frank, a global real estate firm headquartered in London, estimates that although just a third of seniors consider moving into dedicated senior housing, that population will be so large that investors have shown interest in building residential units to suit older consumers around the world.

According to a United Nations report, the number of people age 60 or older is expected to more than double to 2.1 billion in 2050. If just a third of those seniors seek to move to a new home, that’s still a market of 700 million potential customers.

To identify the right mix of age, income, and personal interests for the investors, developers, and business executives it consults, Knight Frank relies on GIS software that can analyse markets in the context of location. The firm can locate concentrations of seniors bearing a trait that distinguishes them from previous generations: economic clout at retirement age and beyond.

Many boomers will turn 65 while continuing to earn a good salary; many others already will have started drawing from substantial retirement plans. Naturally, some segments of seniors may face difficult circumstances—and some have not saved enough for retirement. But the boomer generation as a whole remains an economic dynamo. Already the wealthiest generation, they are expected to control 50.2 percent of net household wealth in 2020.

Investor Interest Rises with the Silver Wave

Where once older people often had limited housing options, now consumer-savvy and financially secure seniors can demand flexible, customizable choices.

More and more, seniors will look for living arrangements that suit their individual needs. That could mean a wellness community that emphasises healthy living and recreation, a housing development with multilingual staff, or top-of-the-line housing for those seeking luxury in their golden years.

In recognition of varied tastes, some edge-seeking businesses and investors are investigating ways to predict where and what kind of senior housing developments will be needed.

Knight Frank uses GIS-powered location intelligence to map out possible business opportunities. “Spatial analysis finds us the right balance of market and demographic conditions, uncovering opportunities particularly suited to individual clients,” says Ian McGuinness, head of the geospatial team and a partner at Knight Frank.

Investors are interested in a range of senior housing projects, including higher-end developments that are essentially subdivisions—or even small cities for seniors. Places such as The Villages, based in Sumter County, Florida, have been highly successful at attracting residents. In fact, a 2018 U.S. Census Bureau report found that The Villages ranked first among all U.S. metropolitan areas in percent population growth. The senior-living development grew from 93,420 residents in 2010 to 128,754 in 2018—an increase of nearly 38 percent.

Once a developer identifies geographic areas where the senior population is expected to grow, the next step is often to use GIS to locate potential properties and determine whether the sites should become communities, apartments, shared dormitory-like accommodations, or even mixed-age developments near a college campus.

GIS-based analysis mixes demographic and commercial market data with predictive algorithms to guide developers to where seniors will be.

Policy Guides Investment

As business leaders and investors explore the strengthening senior living market, some governments are creating guidelines to accommodate this demographic shift, in the same way some areas have imposed rules for including affordable housing in development plans.

In Europe, where 25 percent of the population has already reached 60, the European Union has announced initiatives to prepare for further growth. And in London, governmental authorities have begun developing benchmarks for the amount and type of senior housing that should exist in the city and surrounding boroughs. The New London Plan aims to ensure that a certain percentage of each residential project includes housing for seniors, based on the characteristics and needs of the locale.

That official focus on future needs has helped stimulate interest in senior housing from both operators and investors around the world, including in China and the Middle East, in addition to Great Britain and the U.S. “Finally, it seems that at least a few people have woken up to what’s going on,” says Tom Scaife, who heads up the senior living team at Knight Frank. “We know from colleagues across our network that there’s an impending need in some other countries as well that’s only getting more accentuated.”

To explain the phenomenon to potential investors, builders, and retiree services companies, Scaife and his team plot the results of location analysis on intuitive smart maps.

They use GIS software to analyse and map the relationships among hundreds of pertinent data points such as expected growth of older populations in a region, country, city, or neighbourhood. These smart maps can collate predictions with available space to model development, surrounding retail and recreational opportunities, price points for various groups of retirees, and cost of construction and staffing.

New Precision in Their Sights

Companies are discovering that the data created by digital transformation helps them see where and how business conditions will change. Learn more about their experience with location intelligence.

Finding a Place to Call Home

The location intelligence produced by GIS also guides seniors on decisions about their own future.

“We can analyse cost of care within these housing situations versus cost of care delivered into your own home,” Scaife says. “If you add in other costs like running your home and upkeep, then you can start to build a picture, make an analysis and compare the cost/benefits of relocating at that point in life.”

GIS-based analysis also can include the availability of wellness programs, public transportation, and demographic traits of a neighbourhood such as sex, race, ethnicity, family size, and the lifestyles that seniors enjoy. Results forecast where and how significantly the silver wave will impact not just housing, but other sectors as well.

With predictive capabilities, companies across the business world are using location intelligence to see what competitors have missed, and gain an edge:

- Retail companies are using powerful AI to anticipate where new stores will boost their online sales.

- Oil and gas companies are analysing weather forecasts to understand how to shift resources for maximum efficiency and return.

- An internet service provider is capturing demand signals in GIS and using them to anticipate growth markets.

Tools for New Insight

The European Space Agency recently showed a way to plan for senior housing through location intelligence and a predictive algorithm. Its analytic program looked at census data, economic traits, and land-use patterns to reveal relationships between people and the places they are likely to call home as they age. When applied to a midsized test city, the program predicted the location of older residents with an accuracy of 95 percent.

Given continued advances in cloud computing, ever-more precise data sets, and artificial intelligence, these predictive models will only strengthen—and just in time. Because as seniors in growing numbers assert their consumer muscle, leaders from a wide array of sectors—retail, healthcare, entertainment, government services, and housing—will seek new ways to serve them.

“We’re in a phase where there’s now enough data available for funders to feel more confident about entering the market,” Scaife says. “But at the moment, there’s more capital than opportunity out there.”

However, with an increasing demand for senior housing and powerful research tools to understand how to service it, more businesses may rise on the silver wave.

This article was originally published in the global edition of WhereNext.

Opportunity Awaits Employers That Overcome Location Bias

In a tight job market, every hiring advantage is important. Companies that reduce location bias could gain an edge.

On a résumé, the second thing an employer learns about someone is where they live. A recent study tested the effect that commute distance has on an applicant’s chance of being hired. It found that hiring managers are biased against those who live farther away.

The research, conducted by University of Notre Dame economics professor David Phillips, involved sending more than 2,000 fictional résumés to low-wage employers in Washington, DC. Phillips carefully chose résumé addresses for each job opening and balanced the mix of applicant-workplace proximity and the affluence of the job seeker’s neighbourhood to see how the location of the applicant’s home influenced invitations to interview.

The results: applicants living five or six miles farther from the job received one-third fewer callbacks than those who lived closer.

Distance versus Affluence

The research was designed to test the “spatial mismatch hypothesis,” which argues that the tendency of the urban poor to live far from jobs makes it difficult to find employment, thus perpetuating poverty.

The research offered some solace for job applicants and some insight for employers. Refreshingly, researchers found little significance between the affluence of an applicant’s address and the rate of callbacks, indicating that those in poor areas weren’t purposely being overlooked. Instead, the perceived issue of reliability in a long commute was deemed the deciding factor.

Researchers acknowledged that avoiding applicants with long commutes makes some sense from an employer’s point of view. Neighborhoods with few transit options and high transit costs can translate into a high turnover for low-wage jobs. Long commutes have also been shown to increase absenteeism.

But with location intelligence and creative thinking, employers might find ways to mitigate the impacts of distance.

[To learn more about the effects of location intelligence on a business, read this e-book.]

Influencing Upward Mobility

With today’s booming economy and low unemployment rates, employers face difficulty staffing up to meet peak demand.

Some companies have used a geographic information system (GIS) as a competitive intelligence tool and information resource for finding staff near retail locations.

Location intelligence generated by GIS can also help employers locate pockets of willing and able workers in areas impacted by urban revitalization. The increased cost of living in revitalized areas has pushed low-income, minority communities farther away from economic opportunity and into neighbourhood with little or no access to reliable, affordable transportation.

To access workers and help mitigate the challenges of long commutes, employers might consider flexible options, including four-day workweeks and flexible job hours to avoid busy travel times.

Location Intelligence Maps Solutions

Several commentators suggest that employers would be wise to consider offering shuttle services or public transportation vouchers to improve worker reliability. A modern GIS helps companies map optimal routes to decrease commute times—something that the logistics experts at UPS can attest to.

In addition, companies looking to bolster a social good campaign could focus on hiring in an area where they would have an impact on upward mobility. Location intelligence reveals demographics in specific areas to facilitate this kind of analysis.

Lyft recently announced a partnership with a nonprofit to start the Grocery Access Program, with $2.50 flat fares to grocery stores for families living in food deserts. The resultant improved mobility is helping to address the lack of access to healthy food, a well-documented problem of the urban poor.

A similar effort—one that leverages location intelligence to connect underserved groups with available jobs—could help employers address their own needs and do well while doing good.

A Little-Known Alternative to Wooing Amazon

Across the nation, economic development agencies are quietly nurturing small companies while complementing efforts to attract big corporations.

When Amazon announced in September 2017 that it was looking for a second headquarters location, the news set off a 13-month competition that had 238 cities outbidding each other to woo the internet retail giant with billions in tax and financial incentives. Some observers watched with chagrin. They knew a different way to grow local economies.

The eventual winners—Long Island City, New York, and Arlington, Virginia (along with Nashville, which will host a new operations centre)—awarded Amazon more than $2.4 billion in local and state tax breaks.

The passion with which many cities pursued the expected prize of 50,000 new jobs showed in Columbus, Ohio’s offer of $2.8 billion in direct tax incentives—more than the three winning cities combined. Detroit and Michigan upped the ante to $4 billion and New Jersey was willing to provide $7 billion in city and state tax credits.

But an analysis by The Atlantic highlighted the fact that companies with big tax incentives don’t always meet their goals and may still lure cities into bidding wars every few years. The Brookings Institution also found that many incentive packages do not require the sought-after company to invest heavily in job training for local residents or in improving their living conditions.

Pursuing Titans or Nurturing Homegrown Businesses

For cities that can’t—or don’t want to—compete for market giants, there’s another proven option: economic gardening.

“Chasing the big corporation is expensive, it’s time-consuming, and the likelihood of being awarded that business to your particular community is pretty low,” says John Gendron, who manages the Kansas Economic Gardening program within the Kansas Center for Entrepreneurship, known as NetWork Kansas.

Though rarely in the national spotlight, economic gardening is the lower-cost alternative, free from tax breaks or complicated agreements with multinational corporations that could still pull up stakes if a better deal emerges elsewhere.

The economic development agencies that practice it focus on helping moderate-sized local businesses grow. They do so through research, business consulting, and a technology called a geographic information system (GIS). For companies small and large, GIS reveals new market opportunities, uncovers subtle consumer trends, and tracks demographic shifts in locations across the country and around the world. Economic gardening advisors suggest how companies can turn that deep analysis into profitable action.

The result is locally cultivated economic growth.

Economic Gardening Grows Local Businesses

In Florida, for example, GrowFL used economic gardening to help generate nearly 11,000 net new jobs between 2009 and 2015. Those companies added more than $81 million in net state and local tax revenues, meaning Florida received a return of more than $9 for every dollar invested in economic gardening.

NetWork Kansas’s Gendron, who has worked in economic gardening for nine years, says that this less splashy option often can “spike revenues and create jobs at a lower cost while supporting the businesses right in your backyard.”

Economic gardening can’t promise 50,000 jobs from one company, as Amazon did. But 235 cities spent more than a year and hundreds of thousands of dollars to pitch the internet powerhouse and ended with little to show. Meanwhile the Kansas Economic Gardening Network only needs to spend 45 days and invest services worth $4,500 to help a local company add an average of 12 new jobs and $1.5 million in new sales. Over time, that process can create meaningful job growth without sacrificing local tax revenue.

A Young Company Grows up through Location Intelligence

Rodney Greenup had developed a successful business in Louisiana by providing facilities management and construction services to the oil and gas industry, which requires security clearance for all contractors and subcontractors.

Like most successful entrepreneurs, Greenup relied on great instincts to get his business started and stabilized. He also wanted to keep growing. He thought the simplest way would be to market the services of Greenup Industries in as many states as he could. He was ready to open offices elsewhere and initiate a wide-ranging marketing campaign when he came across the Louisiana Economic Development (LED) agency and its programs. During the approximately 45-day analysis and consultation program with LED, Greenup learned a lot that surprised him.

Location Intelligence: A Smarter Approach

Organizations in many industries use location intelligence to improve their operations. To learn about them, read this e-book on location intelligence.

The agency delivered a slew of economic gardening services, including location intelligence on GreenUp’s customers, competitors, and markets. That GIS-powered insight is often the most important tool in business growth. In simplified terms, GIS is a form of business intelligence that integrates demographic, customer, and economic data into digital maps. Those maps often bring to light hidden or little understood relationships between a company and its current or potential customers.

LED’s research, business consultation, and GIS-based maps led Greenup in new directions.

“Going in, we initially thought we would try to get every client that we could possibly encounter,” Greenup says. “But economic gardening really focused our attention and showed us which potential clients were predicting the largest amount of growth and the biggest spend on their facilities for the next three years.”

Economic Gardening Took Root after Layoffs

Chris Gibbons, CEO of the National Center for Economic Gardening, is credited with helping to originate the idea of economic gardening when he was director of business and industry affairs for the city of Littleton, Colorado, in the 1980s. The idea stemmed from the need to replace approximately 7,000 jobs lost when Littleton’s major employer, a defence contractor, laid off employees into a local economy that could not absorb them.

The methods Gibbons helped develop to stimulate growth set a pattern of similar successes across the nation. During the 20-year period that followed the massive layoffs, Littleton doubled jobs from 15,000 to 30,000 and more than tripled sales tax revenue from $6 million to $21 million—all without recruiting any outside companies, offering tax incentives, or experiencing a large population increase.

Gibbons says GIS-driven insight on potential customers, competitors, and markets allows a typical small business to sharpen its strategy and increase its growth rate from 3–5 percent to 15–35 percent.

[Economic gardening is] an alternative way of doing economic development that focuses on growing local stage-two companies as opposed to attracting outside companies. Both methods work, but I really believe strongly in what we do.

Chris Gibbons, National Center for Economic Gardening

Local Businesses Generate High Percentage of New Jobs

Nationally, the typical business that is a candidate for economic gardening has from 10 to 100 employees and sales of $1 million to $50 million. (Ranges vary in urban and rural areas.)

These are businesses that no longer face a day-to-day struggle to survive and whose owners want to keep expanding but don’t know the best way to market beyond their own location. Often called second-stage businesses, they also happen to generate a disproportionately high percentage of new jobs.

Stage-two businesses may have represented only 17 percent of all US businesses from 2005 to 2015, but they created more than 35 percent of the jobs and sales, according to the Edward Lowe Foundation, which supports the entrepreneurship of second-stage companies.

Digital Watering Holes

One way Louisiana Economic Development helps stage-two companies find opportunities to expand is to show them the digital “watering holes”—websites, blogs, and social media—that potential customers or competitors frequent. This helps young companies stay up-to-date on relevant trends and identify marketing channels that may contribute to their expansion.

Communities in 25 states from California to New York and from Minnesota to Texas have found economic gardening a successful way to grow locally owned and operated businesses. Yet while it’s seen as a cost-effective way of helping homegrown companies expand, it’s often a supplement, not a replacement, for other approaches.

LED, for example, has adopted a multipronged strategy that looks for opportunities at both ends of the business spectrum. The agency works diligently to attract large corporations to the state and retain its current businesses, and it works just as intensely to accelerate the growth of local companies through economic gardening.

For Greenup Industries and others that have gone through the LED program, results have been impressive. Louisiana companies participating in LED’s economic gardening program have collectively added nearly 2,000 net new jobs and increased their gross revenue by $338 million. LED, like GrowFL, calculates a return of more than $9 for every $1 invested in the effort.

“Typically, when we grow what we have, a number of things take place,” says John Matthews, senior director of small business services for LED. “One, the businesses are here already, so they more than likely are here to stay. Two, they understand the culture of Louisiana. And, three, they’re more readily supportive of the community and its quality of life.”

A Michigan pie company learned to increase sales through GIS-powered location intelligence that showed where Michigan college sports fans tended to watch games in West Florida sports bars.

Saving Marketing Costs by Focusing on Core Services and Concentrated Areas

Through GIS technology, economic gardening teams have access to databases that most stage-two business owners don’t know exist. That data can be layered onto smart maps to reveal economic and consumer patterns. For Greenup Industries, the economic gardening team used market research and GIS technology to illustrate some surprising facts.

Not only hadn’t Greenup realized his core business contained services that would be transferrable to the automotive, food services, and pharmaceutical industries, but also that those same businesses were growing at a faster rate than his oil and gas clients.

Moreover, by using location intelligence to find clusters of potential new clients within those overlooked industries, LED was able to show that he had many more opportunities in the Gulf Coast states of Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida than he had imagined. It caused Greenup to rethink his strategy of opening offices in far-flung locales.

“You have to listen to the data,” Greenup says. “Economic gardening really clarified a lot of things for me… I really thought I had a good plan for where I was going, but what they did was make me focus and realize my other plans would be distractions and an inefficient use of time and money.”

Variety of Crops Arise from Economic Gardening

The array of businesses helped by economic gardening stretches over many market sectors and includes both B2B and B2C companies.

- In Louisiana, LED showed a company that manages the vegetation affecting powerlines how to expand significantly, and it also helped map an expansion for a software company that developed an app that restaurants can use for delivering to-go orders.

- The National Center for Economic Gardening has helped many companies expand nationally while keeping their local roots. One example: A Michigan pie company learned to increase sales through GIS-powered location intelligence that showed where Michiganders had migrated, where customers with similar tastes might live, and even where Michigan college sports fans tended to watch games in West Florida sports bars.

All are reminders that job creation and revenue growth through smaller businesses can add up over time and even begin to compare favourably with efforts to land a giant corporation. And some second-stage companies nourished by economic gardening will become tomorrow’s household names.

Having grown larger through the crucial location intelligence that economic development agencies provided, these companies may be more likely to stay rooted in their hometowns.

“We need to nurture second-stage companies,” says Matthews of Louisiana Economic Development. “Because the data suggests they are the companies that will create jobs today and in the future.”