Blog Archives

Post navigation

The Hidden Factor Affecting Employee Health

It’s time for employers to wake up to an overlooked–and costly–aspect of employee health.

Nearly 80 percent of big businesses, and a growing number of small and midsize companies, self-insure their employees’ health coverage. On average, that costs a business more than $13,000 per employee per year.

Most companies have also instituted wellness programs to improve the health of workers and decrease healthcare costs. Unfortunately, many wellness programs are not as effective as they could be because they overlook a key data point: the health implications of where an employee lives.

Research has proven that location carries with it many social, community, and environmental conditions that affect a person’s health—also known as social determinants of health. The impact of these factors reaches far beyond one’s home. It follows us everywhere we go, including into the workplace and the healthcare system.

Experiments in places such as Camden, NJ, have shown a greater than 50 percent reduction in healthcare costs for patients in certain geographies. With that in mind, employers who use location intelligence to analyse social determinants of health can create data-driven wellness programs designed to overcome barriers to good health and potentially cut costs.

While corporate executives routinely use data to drive business decisions, many of those executives are still investing in generic wellness programs designed without employee context.

Innovation in Your Inbox

Sign up for the Esri Brief, a biweekly email that connects senior executives and business leaders with thought-provoking articles on location intelligence and critical technology trends.

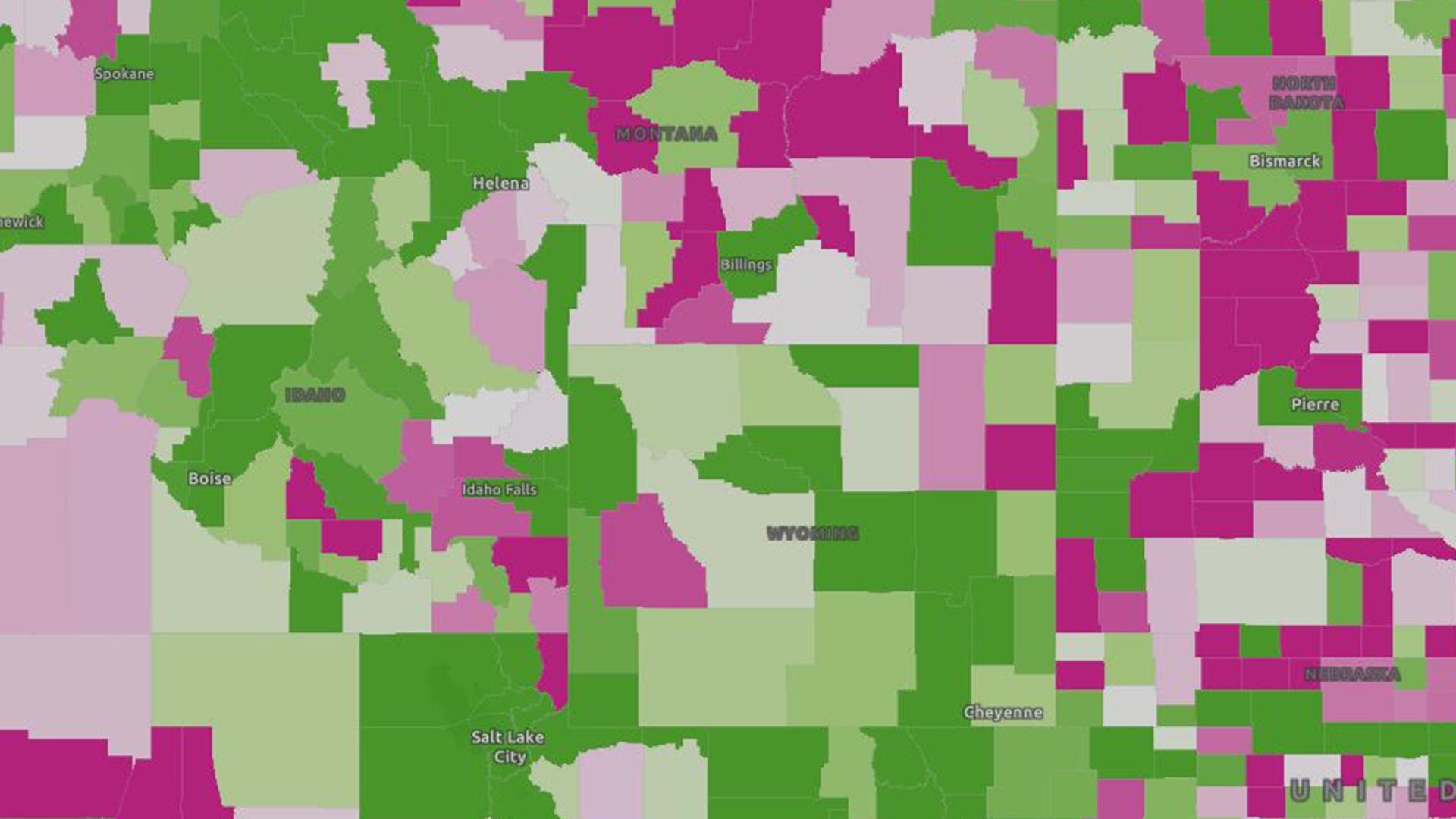

The US Centers for Disease Control says too few employers are using effective, science-based workplace health programs that address unique challenges faced by employees. A geographic information system (GIS) allows companies to identify social determinants of employee health by creating a wellness map that identifies top inhibitors of a healthy lifestyle based on where employees live. Such technology can also reveal health-promoting resources in those same communities.

Today’s Corporate Healthcare and Wellness Landscape

In 2016, the number of companies that self-insured at least one health plan reached 41 percent, up from 30 percent in 2000. Self-insurance has the potential to offer employers significant financial advantage, but only if they can control costs.

Corporate wellness programs were introduced in the mid-1970s to address employers’ cost concerns by encouraging employees to adopt and maintain healthy behaviours. Johnson & Johnson’s trailblazing Live for Life program began in 1979 and included a questionnaire and physical exam. The company subsequently provided employees customised wellness support including fitness, nutrition, and stress management tips.

Since then, the market for corporate wellness has grown significantly. Ninety-nine percent of firms with 200 or more employees offered at least one wellness program in 2013, according to one study. Of those employers, 69 percent offered gym membership discounts or on-site gyms, 71 percent offered smoking cessation programs, and 58 percent offered weight-loss incentives.

The reasons for such programs are clear. For example, compared to employees of healthy weight, obese workers may incur more than double the cost for healthcare, workers compensation, and short-term disability. That could add up to an additional $4,000 per year, per employee, one study found. Additional health complications such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol drive that number even higher.

The Effects of Location

Location can affect a person’s health in many ways, including:

- Access to healthcare, services, education, and healthy food

- Community characteristics such as crime rate, traffic, and availability of public transportation

- Environmental exposures like pollution, pollens, and toxic waste

- Socioeconomic factors that affect a person’s ability to attend medical appointments, access healthy food options, or exercise in a safe place

The Missing Element: Location

Extensive research has been conducted in recent years proving that a person’s environment directly impacts the ability to live a healthy lifestyle. The world is beginning to take notice, as evidenced by a December 2018 tweet from U.S. Surgeon General Jerome M. Adams:

Ana Lopez-De Fede, Ph.D., research professor and associate director of the Institute for Families in Society at the University of South Carolina, has studied how a person’s place of birth and where they live influence their work environment.

For example, in a single-vehicle household, one family member typically takes that vehicle to work, limiting the rest of the family’s access to resources like grocery stores, workout facilities, and libraries. Those family members miss medical appointments more frequently, and the lack of routine visits ultimately leads to a higher rate of preventable emergency rooms trips and inpatient hospitalizations.

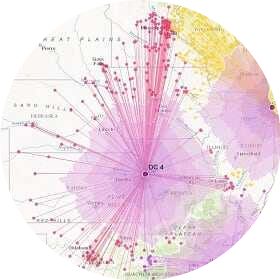

But the single-car phenomenon is just one of many factors that influence employee health. Others include the rate of particulate matter in the air where they live, access to exercise opportunities and healthy foods, and the ratio of local primary care physicians. Plotting these social determinants of health on a GIS-driven map can give employers a better sense of what ails employees—and what drives healthcare costs. That awareness often leads to innovative remedies.

To explore a few of the social determinants of health in your neighbourhood, click through this map. (To view each factor on its own, deselect all other factors.)

“Utilizing GIS, an employer can determine the reasons behind high medical costs by understanding context as it relates to employees’ geographic location,” says Lopez-De Fede. “An employer can then determine reasonable costs of healthcare and create contextually relevant wellness programs that improve the quality of life of their employees, while also addressing those high medical costs.”

Academic studies have confirmed Lopez-De Fede’s findings. The National Research Council found that a variety of place-based influences can affect health, including physical circumstances (e.g. altitude, temperature, and pollutants), social context (e.g., social networks, access to care, perception of risk behaviours), and economic conditions (e.g., quality housing and access to health insurance).

Another study found that the increasing epidemic of obesity and chronic disease is likely influenced far more by food and eating environments than by individual factors such as knowledge, skills, and motivation. The finding underscores the importance of making the healthy choice the easy choice, a mantra in the public health community.

Location Viewed as the “Seventh Vital Sign”

Business executives can take a cue from healthcare practitioners such as Lopez-De Fede, who are now examining location-based determinants of health for each patient.

Southern California’s Loma Linda University Health has created personalized “wellness maps” for each of its patients, based on the belief that location is one of a patient’s vital signs.

Loma Linda creates the maps using GIS technology, digitally layering information on top of geographic locations. Each patient can access a personalized GIS wellness map through Loma Linda’s patient portal for electronic health records. On the map, the patient sees her personal health resources (clinics, providers, labs, and pharmacies) as well as community resources such as bus transportation routes, and places to exercise or purchase nutritious food. Each map is updated as the patient’s diagnosis changes. For example, an expectant mother will see a very different map than a patient with diabetes.

For some employees, the opportunities for healthy choices are significantly limited based on where they live, which can ultimately impact the cost of their healthcare.

The County Health Rankings & Roadmaps Project

Utilizing Location Intelligence to Improve Wellness in the Workplace

Self-insured businesses are already driving healthcare innovation in the workplace by offering new care models like telemedicine and on-site clinics. The next step will be using GIS-based location intelligence to develop more effective health and wellness programs.

Dr. Lopez-De Fede says employers should begin by asking themselves questions related to their employees’ unique health challenges and associated costs, such as, Where do my employees live? What’s going on outside of the office?

GIS helps employers answer these questions by analysing health-related information in the context of location. Data is gathered at a group level to protect employee privacy, and its analysis can help employers find solutions to health barriers. For instance, if employees aren’t picking up prescriptions or are missing doctor appointments, an employer could create an in-network pharmacy closer to the office and create flex time for appointments.

Once employers have used location intelligence to identify employee barriers to health, they can create more effective wellness programs that address location-based challenges faced by employees. Examples include:

- Develop key partnerships in employees’ communities to improve access to and awareness of wellness resources such as pharmacies, fitness clubs, grocery stores, and transportation resources. (The North Carolina Institute of Public Health in partnership with the Carolinas HealthCare System is doing this for its patients, using GIS.)

- Add to the insurance network pharmacies and health clinics in underserved neighbourhoods

- Allow employees to have groceries delivered to the office and provide them a place to store them

- Provide free exercise classes in the workplace, and hold a 5K walk/run in underserved communities

- Decrease stress associated with long commutes by offering shared transportation options (e.g., vans, carpools)

- Create a teacher mentorship program to transfer best practices from healthy communities to less-healthy communities

- Offer an app that lets employees and their families build an exercise routine based on nearby green spaces, bus routes, gyms, bike shares, sunrise/sunset times, and more

- Create personalized wellness maps that show employees resources in their communities

Wellness programs are often designed with the best intentions and the hope that they balance good health with good economics. But in the age of data-driven decisions, employers can use more than hope to drive results. Innovative, self-insuring companies are now using location intelligence to help promote employee health, reduce costs, and improve productivity.

As Supply Chains Falter, Executives Ask, “What If?”

Exploring three keys to supply chain visibility: good location data, intuitive visuals, and what-if planning.

When one link in a supply chain breaks unexpectedly, executives with visibility into the entire network excel at launching backup plans to minimise disruption and protect sales. For those without supply chain visibility, desperation can set in quickly.

That happened this summer when one business seeking a new supplier of refined sunflower oil emailed a Georgia farm, as reported by Civil Eats. The business requested 50,000 metric tons per month, but the farm’s average output fell a bit short: 34 metric tons a year.

Until recently, Ukraine had been a go-to exporter of sunflower oil, which is used as cooking oil and in packaged foods and cosmetics. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sent companies scrambling for alternate supplies.

When the unexpected occurs—whether it’s a war, a natural disaster, or a pandemic—manufacturers, distributors, and retailers must pivot with remarkable speed. Today’s supply chain executives have discovered they need more than inventory management solutions geared toward stocking warehouse shelves.

Those who stay ahead of supply chain disruptions use geographic information system (GIS) technology to see where materials and finished goods are in the supply chain, and test trade-offs between factors such as suppliers, costs, speed to market, and net-zero goals.

Article snapshot: As economic conditions fluctuate, smart supply chain executives are using location data to visualise logistics strategies and test what-if scenarios.

Mapping Every Step toward Supply Chain Visibility

Supply chain visibility has been key to overcoming recent disruptions. But a logistics strategy grounded in visibility isn’t just about navigating extreme moments; it also helps executives deliver products to market under calmer circumstances.

Speaking at a recent supply chain industry conference, one pharmaceuticals executive stressed the importance of mapping all phases of a company’s supply chain, from planning to procurement, manufacturing to distribution.

Only when executives have a clear picture of each supply link can they effectively manage their network, according to McKinsey. The consulting firm says three practices are key to avoiding supply chain disruptions: visibility, scenario planning, and comprehensive, reliable data.

Global leaders in manufacturing, distribution, and retail use GIS technology for all three.

A Complex Picture, Simplified

GIS acts as a single source of truth for locations throughout the supply chain—showing shipping routes, distribution centers, and supplier facilities across every stage of production. GIS treats each as an information layer that executives can toggle on or off on smart maps, creating the visibility needed to understand complex global relationships.

When unexpected events occur—or even before they do—planners use the technology to run what-if scenarios, weighing the outcomes of changing a route, a supplier, or a strategy. The data science behind those GIS simulations is called GeoAI–or geospatial artificial intelligence. As Esri’s Wendy Keyes explained in a recent WhereNext Think Tank:

We set up a GeoAI model to focus on a particular goal—that could be minimizing emissions, maximizing equity, or minimizing weather risk. Then we define the other factors involved—customer satisfaction, revenue, profit, etc. This is where the power of simulation comes in. . . . We’re not predicting the future yet, but we are getting much better at anticipating outcomes and making better decisions based on that insight.

GeoAI can be used in tandem with another GIS technique that displays complex supply chain relationships in intuitive knowledge trees. Such visuals help business leaders understand how an event’s effect on one supply tier will ripple to others. Seeing that information in a geographic context can illuminate key dependencies among suppliers and strengthen contingency plans.

No matter how the next disruption develops, companies that manage supply chain data in GIS will be prepared. With that foundation, executives can visualise critical links and plan effectively by modeling scenarios before taking decisive action.

Global Demand for Nickel Soars—Will Biodiversity Suffer?

Nickel miners are caught between increasing demand and the rising focus on how mines affect biodiversity. Location analysis is helping.

As electric vehicle battery makers use more nickel to produce greener vehicles, nickel miners face a conundrum: How do they extract the metal from the ground in the name of sustainable transportation—without compromising sustainability in the areas they’re mining?

Some are using biodiversity offsets to balance their impact on nature, and new location analysis reveals that in at least one case, the practice appears to be working.

Article snapshot: Nickel miners are increasing production to support electric vehicle battery manufacturing, but how that surge will affect local biodiversity is unclear. Some observers are using location analysis to find out.

Rising Demand Tests Nickel Miners

The growing market for electric vehicles, which require nickel for their batteries, will nearly double the global demand for nickel by 2030. Analysts question whether the current mining infrastructure can handle the need.

A 2020 McKinsey report asked another question—whether nickel miners can expand while satisfying environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) benchmarks. A new study in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Sustainability, which analysed efforts to limit biodiversity loss near a nickel mine in Madagascar, offers a qualified yes. The findings are good news for any company taking a geographic approach to ESG goals.

Biodiversity and ESG

Biodiversity preservation is increasingly seen by ESG-minded companies and investors as equally important to stemming climate change, according to recent reports.

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) says that biodiversity depletion could cost the global economy $10 trillion in lost “ecosystem services” by 2050. Many companies concerned about their impact on biodiversity are adopting a location intelligence strategy, according to the WWF, using geographic information system (GIS) technology to understand complex environmental data.

The concept of climate change offsets is straightforward: if a company is responsible for a certain amount of emissions, it takes steps to remove an equivalent amount of emissions from the atmosphere.

The owners of Madagascar’s Ambatovy mine applied the offset model to biodiversity loss. Specifically, they attempted to compensate for any deforestation caused by nickel mining by working to prevent deforestation nearby, much of it from agricultural activities.

In the Nature Sustainability study, independent scientists used models to predict how much deforestation would have occurred without the nickel miner’s offsets. Through maps and location analysis, the authors concluded that the offset efforts are on track to prevent an equivalent amount of deforestation.

The Limits of Offsets

The idea of applying offsets to biodiversity loss is controversial, the scientists note. For instance, offsets can complicate issues of equity, such as the fact that some of the deforestation prevented near the Madagascar mines would have involved small farming.

Furthermore, the authors point out that deforestation is an imperfect proxy for biodiversity loss. Unlike climate change offsets, which rely on clear metrics such as carbon and methane emissions, the components of biodiversity can be difficult to isolate.

Still, the study of nickel mining in Madagascar shows that offsets of biodiversity loss are possible—and that with effective location analysis, the success of these efforts can be assessed.

Biodiversity as a Shared Effort

For companies committed to biodiversity as a component of their ESG policies, the study’s takeaway is not that offsets are a cure-all; rather, the lesson is that any offset program should be carefully evaluated, and that location intelligence provides a useful framework to do so.

In addition to helping scientists take a data-based approach to assessment, GIS-based maps and analyses can promote transparency and collaboration among disparate actors.

Using location intelligence, companies that partner with NGOs and governments on biodiversity offsets can analyse and share progress regularly. That kind of evaluation can propel biodiversity from an abstract ESG goal to a data-driven reality.

A “Second Skin” for Buildings Aims for a Net-Zero Future

A new retrofit process with net-zero aims adds a "second skin" to existing buildings, raising questions of local context.

The built environment accounts for nearly 40 percent of energy-related CO2 emissions. Building operations cause the majority of emissions due to poor insulation, electricity generated by fossil fuels, and other factors. The rest comes from “embodied carbon”—emissions created during the manufacturing of building materials and the construction process.

Article snapshot: Buildings create significant carbon emissions, and we’re stuck with two-thirds of our existing buildings for at least the next two decades. Fitting some with a “second skin” might help, and a geographic approach could increase the benefits.

Even if professionals in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) trades limit embodied carbon in new projects, an estimated two-thirds of the world’s current indoor space will still be in use in 2040. For property owners and developers, retrofitting buildings to become carbon neutral is costly and time-consuming, but it may also be a competitive advantage in attracting conscientious renters and buyers. Luckily, innovative solutions are emerging—including the idea of a “second skin” for existing buildings.

Applying new techniques with a geographic approach will likely speed up their rollout and boost their efficacy as carbon-neutral fixes.

From Scan to Second Skin

A recent Fast Company article highlighted Berlin-based startup ecoworks, which is pioneering a second-skin retrofitting process. The process begins with 3D scans of a building’s facade and interior taken with a handheld device.

This digital twin is sent to a factory, where a highly automated process yields panels that fit over the building like a second skin, with room for windows, pipes, and ventilation shafts. The process of installing the panels, along with a modular roof equipped with solar technology, is said to take just a few weeks.

Throughout the AEC and real estate industries, 3D scans are now commonly incorporated into building information modeling (BIM) software. Many AEC professionals augment BIM images by importing them into a geographic information system (GIS), which reveals how buildings will look within landscapes and streetscapes, as well as how they will interface with infrastructure like sewers and cables.

Beyond these visualisation capabilities, the merger of GIS and BIM delivers operational advantages. Project managers can streamline design and build operations by integrating the technologies, and building managers can analyse and quantify energy efficiency.

Efficiency and Speed

Streamlined project management is the most immediate benefit this technological merger can bring to building retrofits.

Installing a building’s second skin requires coordination among diverse stakeholders, including property owners, factory staff, construction crews, and local building departments. Cloud-based GIS can serve as a common visual meeting ground for a retrofitting project, promoting innovation and fostering collaboration.

For retrofits involving large developments or communities, a GIS-BIM combination enhances progress by integrating authoritative data and generating dynamic colour-coded maps that can be observed at a central office or in the field.

The merger of BIM and GIS could also help planners coordinate building retrofitting with other projects designed to counter the effects of climate change. These might include planting trees to decrease heat islands or finding high-potential sites for solar arrays.

Blocks of Opportunity, with Savings to Quantify

With millions of buildings in use today, planners must identify those best suited to structural retrofitting and second skins.

Experts have suggested that AI could speed up identification of the best candidates, which tend to be blocklike apartment buildings. GeoAI, a hybrid of GIS and AI technologies, could accomplish that by highlighting hundreds—or even thousands—of buildings from aerial photographs. As retrofitting technology improves, machine learning models could be trained to find new candidates.

Once buildings in an area receive the second-skin treatment, the GIS-BIM combo could help quantify decarbonisation efforts, as described in a recent NextTech article.

The calculations would be complex, including an account of emissions avoided through improved insulation and solar energy production. Since the second-skin concept means that most of a building’s facade is retained rather than destroyed, even embodied carbon savings could factor into computations.

As with any solution to the climate change problem, implementing a building’s second skin requires an organised and dedicated effort. A foundation of GIS technology, augmented by BIM and AI, provides the collaboration capabilities and the all-important local context needed to support a critical global effort.

Finding Our Way in the Metaverse

Experiences range from buying real estate and furnishing a virtual home to attending a concert or interacting with holograms of your coworkers.

Nearly nine out of ten executives expect to find business value in the metaverse in the next five years. Others aren’t sure what the value will be—or even what the metaverse is. Still others are already knee-deep in defining both.

Article snapshot: If the metaverse has you confused, you’re not alone. Some have tried to simplify things by calling the metaverse “the internet with a sense of place.” Here we look at what that might mean in the digital worlds of today and tomorrow.

Take Everyrealm, owner of the MetaMall in Decentraland. The digital shopping centre offers 364,000 square feet of space to companies interested in creating retail storefronts for virtual shoppers. The mall doesn’t exist in the real world, but Everyrealm expects it to generate real profits, and recently engaged real estate firm Avison Young as the listing agent for the virtual retail space.

The emergence of shopping in the metaverse shouldn’t come as a surprise. Given the chance to create unheard-of experiences in a new cyber realm, many companies are opting for a more familiar, less risky path—replicating the world we already inhabit, right down to the malls.

It’s a natural next step as the internet weaves itself more intimately into consumers’ lives. Forward thinkers like Accenture’s Katie Burke have called the metaverse tomorrow’s internet, with at least one key addition: a sense of place.

Indeed, whether we visit the metaverse to shop, socialize, play fantasy games, or work, it’s likely that understanding place—where we are, what we encounter there, and how we navigate in and around those places—will be as important as it is on terra firma.

Who Does Your PR?

Eighty-six percent of Turkish residents are familiar with the metaverse—the strongest name recognition in any country, according to the World Economic Forum. (India and China are second and third.)

By contrast, the metaverse could use a PR boost in Poland, France, and Belgium/Germany, where only 27, 28, and 30 percent of residents, respectively, have heard of it.

The Metaverse: Finding Our Way

If you’ve never been to a virtual mall in Decentraland and don’t know which cryptocurrency to use for real estate purchases in the The Sandbox, don’t worry, you have a lot of company. The metaverse is a phenomenon billions of people have heard of and few have experienced. Just 16 percent of Americans could even define the metaverse in a recent survey.

But that doesn’t mean it won’t be part of our future. After all, it’s already an artefact of our past. Nearly a generation ago, Second Life and other digital worlds emerged, earning enthusiasm from users and investments from corporations as well as some scepticism.

Today’s metaverse is much improved, proponents say, thanks to better 3D visuals, more evolved interactive virtual and augmented reality, tactile experiences, and cryptocurrency-based transactions.

But the allure remains: The metaverse is a place where one can virtually interact with friends or strangers, experience games, collaborate on work, and purchase products and services.

As with any new land, its geography is worth exploring.

Despite its potential for creating entirely new geographies, many versions of the metaverse are tethered to traditional ideas of place.

What’s the Plural of Metaverse?

Despite its all-encompassing name, the metaverse isn’t a single place with a central gateway. Rather, it’s a panoply of experiences, each accessed separately and governed by its own company, creator, or decentralised collective of users.

Some realms are accessed through VR goggles; others can be navigated via a desktop browser or a phone. Experiences range from buying real estate and furnishing a virtual home to attending a concert or interacting with holograms of your coworkers around a cyber conference table. Prominent destinations include Roblox, Decentraland, Meta’s Horizon Worlds, The Sandbox, ZEPETO, games like Grand Theft Auto, and others.

On the Metaverse To-Do List

For more on what one can do in a metaverse, check out this list—or read about one Vice reporter’s recent virtual night out.

Such diversity has led to discussions of what qualifies as a metaverse, a multiverse, or an omniverse. One antidote to complexity in any new realm is to establish a sense of place—and a means of navigation. Humans have relied on maps to navigate the real world for millennia, and 50 years ago, technology called a geographic information system (GIS) emerged to deepen that relationship by adding information that helps people better understand a location.

Since then, innovators have applied GIS to many challenges and opportunities. One pioneering biochemist used the technology to map DNA strands in an effort to share information about COVID-19 and other diseases. Others have used GIS to create realistic cities for Disney movies and digital twins for infrastructure projects.

In the spirit of innovation, here we explore some of the main uses of the metaverse and share a few thoughts on how location—and location technology like GIS—might factor into each:

- Gaming—Traditional video gaming is migrating toward mixed reality, where virtual actions are overlaid on the real world through augmented reality or on a manufactured world through virtual reality. In a recent presentation, Rochester Institute of Technology professor Brian Tomaszewski called Pokémon GO a prime early example of the former. He also noted that GIS technology is increasingly involved in simulating experiences in business settings. That might include the models AEC firms use to review projects with clients or digital twins used by city leaders to plan for growth.

- For more on the intersection of gaming and GIS, read Rex Hansen’s blog on location-aware plug-ins for game engines like Unity and Unreal.

- The Third Place—In the real world, the third place is where people spend time outside work and home—in restaurants, coffee shops, movie theatres, concert halls, stores, bars, clubs, and the like. In the metaverse, Meta (née Facebook) has been an early player in creating digital spaces where people socialize, but other metaverses boast similar experiences. Location technology could play a key role in helping users navigate these spaces and understand relationships among people and places. It might also help businesses understand the popularity of stores or the ways in which avatars move through virtual spaces.

- Work—While some companies will lease space in the metaverse as a way to market to customers, others are exploring how employees can collaborate or improve daily activities. Augmented reality could be a boon for maintenance technicians and field operatives. WhereNext covered the story of an IT director who saw a chance to improve safety and efficiency for his colleagues at a water utility in New Jersey. Through the integration of GIS software, HoloLens mixed reality glasses, and a geodatabase, he enabled technicians to see holograms of underground utility lines, helping them avoid gas or telecom lines when repairing a water leak.

On a Path Toward New Experiences

On a recent S&P webcast, one expert suggested it would take half a decade for a robust metaverse to emerge. In a 2022 Pew poll of tech leaders, 54 percent said a robust, immersive metaverse would be part of daily life for millions of people by 2040.

If its beginnings are any indication, the metaverse will likely evolve in many ways. There will be opportunities to game; meet new people; and extend the way we work, shop, and socialise. In all those activities, our desire for a sense of place and novel locations will guide our experiences.

What those experiences will be, only time will tell. In the meantime, maybe we’ll see you at the mall.

An Executive View of the Global Economy

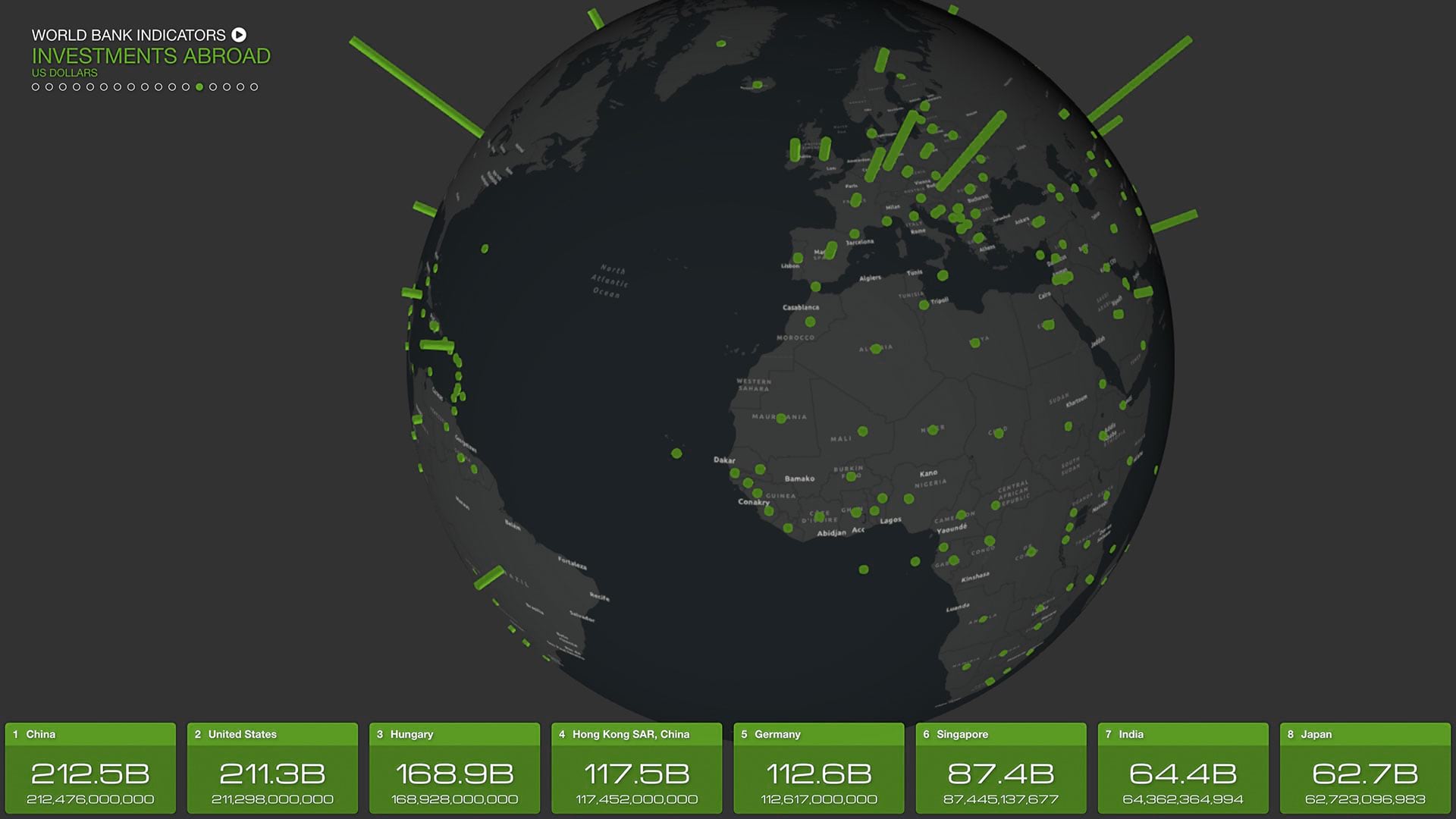

In the demo, GIS captures a geospatial view of World Bank data on global indicators like population, CO2 emissions, foreign investment, and ...

In his book The Raging 2020s, author Alec Ross posed a question that hints at the current state of global business: Does every company now need its own state department? Global 2000 business leaders are confronting a complex international landscape in which risks—and opportunities—can come from any direction, with little or no preamble.

Article snapshot: Global 2000 executives can monitor the world economy on a 3D map, toggling between key metrics, zooming in to specific countries or regions, and planning investments or adjusting supply chains based on what they see.

With supply chains, offices, and assets spread across continents, executives need real-time awareness of global indicators and economic signals that could impact their operations. Many corporations today use geographic information system (GIS) technology to supply an interactive picture of global affairs or company operations.

The 3D map in the video below, displaying international economic metrics on a GIS-powered digital globe, demonstrates the kind of spatial context that C-suite leaders need to navigate a global business environment.

A Geographic Approach to Global Indicators

In the demo, GIS captures a geospatial view of World Bank data on global indicators like population, CO2 emissions, foreign investment, and imports and exports. At a glance, business leaders can monitor the state of international trade or zoom in to view data on a particular country.

By seeing global indicators in 3D instead of on a spreadsheet, executives can more easily spot trends or interconnections driven by geography. For instance, the GIS rendering showing CO2 emissions in Germany relative to the rest of Europe could influence investment policy at a company that’s enacting the principles of spatial finance.

A supply chain executive studying the map might investigate why Vietnam’s exports exceed those of surrounding southeast Asian nations. Complementary data on foreign investments or inflation could lead the executive to explore a new trade route or supplier.

A GIS analyst could tailor the map to a company’s priorities by customizing the view, allowing a COO to highlight countries where the company does business or where it is considering investments.

Seeing the World in New Ways:

Visit the Cool Maps site for an interactive version of this map and other fascinating glimpses into the way we live and do business.

A Central Nervous System for Business Intelligence

A 3D map of global indicators shows the value of GIS as a central nervous system for business intelligence. Just as the human brain turns sensory experiences into information to help us make decisions, GIS transforms disparate data from the World Bank and other sources into maps that guide corporate strategy.

In an interconnected global economy, executives can’t base decisions on isolated data points. Location intelligence provides a holistic view, revealing how a piece of information like population levels in China or access to electricity in Brazil fits into a larger operational context.

Globalization has given companies access to more markets while exposing them to greater risk. When considering whether to open a new mine overseas, a modern natural resource company can’t simply analyze cost and demand. Environmental impacts, geopolitics, and the potential for local social unrest could just as easily make or break a venture.

Location intelligence reveals global indicators and local realities in an intuitive view, helping business leaders make data-driven decisions. With GIS, global enterprises and small businesses alike have ready access to insights worthy of a state department briefing.

Supply Chain Squeeze Spotlights Smarter Use of Resources

Knowing where and how to use limited resources is a strategy that leaders across multiple industries are working to master.

In the face of constricted supply chains, manufacturers and their customers have had to embrace a business cliché: do more with less.

Article snapshot: Challenged by high product costs and low availability, companies can adopt more precision in where and how they use certain goods.

The scarcity of supplies—from cars to baby formula to coffee—has led some businesses to reengineer their supply lines to use fewer sources of raw materials or components. In turn, their customers have had to become more strategic about how they use the products they buy.

For the agricultural industry, one critical ingredient has been increasingly hard to come by. As Bloomberg Businessweek recently reported, supplies of synthetic fertilizer were already stretched thin by rising natural gas prices, factory closures, and export restrictions when Russia, long an exporter of crop nutrients, launched its invasion of Ukraine, stretching supplies even thinner.

For farmers, maximizing the impact of fertilizer may be a challenge best accomplished with maps.

Precision Preserves Scarce Resources amid Fertilizer Shortage

Knowing where and how to use limited resources is a strategy that leaders across multiple industries are working to master.

For farmers, strategically placing fertilizer to maximize its nutrient benefits isn’t just possible, it’s already happening.

Iowa Select Farms, the fourth-largest hog producer in the US, created its own app powered by geographic information system (GIS) technology to ensure that hog manure gets strategically—and responsibly—applied to the crops that will eventually feed its hogs. By integrating data on soil analysis into GIS, the company determines which sections of a farm need fertilizer applications and to what degree.

As reported in a recent WhereNext article, the Iowa Select team “turned to GIS to analyse how much fertilizer to apply to which portions of the fields in accordance with environmental regulations—a form of location intelligence pivotal to smart agriculture.”

From Fertilizing to Harvesting, Precision Begins with Location

The benefits of a strategic, geographic approach to farming aren’t limited to fertilizer application. As technology has advanced, agribusinesses have deployed drones and field sensors for crop and soil monitoring—part of a movement some call the smart farm. The resultant data, when analysed with location technology, can yield valuable insight that guides planting, weeding, and harvesting.

Such knowledge also informs purchasing by better matching inputs to outputs, which can help control costs and increase yields while providing more predictable forecasts for the manufacturers who rely on agricultural products.

Some smart farms (also known as connected farms) are also assessing crop health from the sky, limiting the need for costly in-person visits. As noted in this WhereNext Think Tank interview:

The connected farm is a broader vision of precision agriculture, which has been around for decades. Technology plays a key role—it’s changing how farmers look at a field of corn or the next crop of grapes or a herd of cattle. With new technology and data, growers and ranchers see in a very nuanced way how each location within their operation is performing and adjust proactively.

A shortage of fertilizer may ultimately spur more efficient farming techniques, which would be a welcome outcome in a world facing a growing population and increasingly severe impacts from climate change. The key in times of scarcity is having the location intelligence to know precisely how much product to apply and where.

What Is Spatial Finance, and How to Prepare for It

Spatial finance is helping banks, insurers, and even companies themselves gauge the impact of business activities on the natural world.

The ubiquity of climate change disruptions and the urgency of a green economy are driving financial decision-makers toward a new class of calculations when considering investments and partners.

Article snapshot: Businesses worldwide are under new scrutiny from a practice known as spatial finance, by which banks, insurers, and other financial players use GIS technology and spatial data to assess a company’s impact on the world around it.

Estimating returns on logging a plot of timberland may be a familiar exercise—but what’s the value of not logging it, and instead generating offsets to sell in the carbon market? A sugarcane mill located near Costa Rican rain forests might offer low production costs, but board members may ask whether it is worth the reputational risks posed by its environmental impacts. An investment team considering a mining opportunity in Australia might ask how exposed the assets are to the threat of wildfire.

For those holding the purse strings of the global economy, the ability to quantify and analyse the effects of business on nature, and of nature on business, is becoming an essential competitive advantage.

A specialized brand of spatial finance—a term coined by Oxford University’s Sustainable Finance Group—has arisen to meet the demand for such insights.

Spatial Finance: Assessing Sustainable Risk and Opportunity—From Earth and Space

This new application of spatial finance relies on a suite of innovative technologies including a geographic information system (GIS), remote sensing, and artificial intelligence (AI) to generate insights on sustainability-related risks and opportunities in locations around the world.

The near real-time speed of imagery and information generated by satellites, drones, or IoT sensors has made spatial finance attractive to bankers who are well-versed in high-frequency data. Machine-learning algorithms rapidly process images and sensor readings of forests, coastlines, or cropland, spotting anomalies or patterns on a global scale.

GIS enables lenders and advisers to map and analyse these findings via a geographic approach that incorporates business infrastructure, supply chains, and insurance policies. From this holistic operational view emerges a powerful form of location intelligence—one that allows executives to anticipate places where business and sustainability priorities might clash or successfully merge. They can then tailor strategies accordingly.

David Patterson, head of conservation intelligence at the UK branch of World Wildlife Fund (WWF), has seen significantly more interest in spatial finance—and a related practice referred to as geospatial ESG—in just the last six months. “It’s only going to be a matter of time until we see this more and more mainstreamed,” he told WhereNext.

When a company’s sustainability practices—or lack thereof—impair its access to financing, its cost of capital, or its insurance eligibility, sustainability quickly becomes a C-suite issue.

Geographic Location: The Nexus of Nature and Finance

Spatial finance is predicated on the idea that geographic location, the natural environment, and economic outcomes are interlinked. Those who can discern patterns and trends in those relationships—and factor them into decisions about whether to back a startup or write an insurance policy—can minimize losses and safeguard returns.

No less an authority than Adam Smith, the forefather of capitalism, attested to the power of location to influence financial fate. In his landmark tome The Wealth of Nations, Smith notes how countries with access to coastlines, which facilitated trade, outperformed those situated inland. In the 21st century, it matters not only how close a company is to resources, but also how it treats those resources. Spatial finance makes it harder for companies to hide harmful activities.

The practice can be employed by investors and insurance firms to analyse would-be partners or customers.

It can also help companies analyse their own operations around the world and understand areas of risk.

Many firms first turn to spatial finance for help with a pressing need: identifying climate risks, ideally before the worst-case scenarios come to pass. The eruption of wildfires in Australia—estimated to have caused over $4.4 billion in economic damage—was a flash point for the Swiss private bank Lombard Odier. To better assess how such natural catastrophes threaten business assets and infrastructure, the firm engaged geospatial consultants.

By interweaving satellite imagery with data on temperatures, wind speed, and humidity in the affected Australian regions, the Lombard Odier team determined that wildfires could have been predicted using the toolset of spatial finance. As reported in Bloomberg, geospatial analysis is now an input in investment decisions at Lombard Odier.

As investment banks, data providers like S&P Global and Refinitiv, and third-party consultants and watchdogs like WWF dedicate more resources to spatial finance, business executives are taking note. Companies that use GIS software can plumb thousands of data layers that are updated daily or weekly on measures likes heat indexes, water quality, and deforestation. Even a basic geospatial capability can help CEOs anticipate the sustainability-related issues that financial institutions, insurers, and other business partners might flag.

“GIS is the anchor point,” says Pablo Izquierdo, GIS lead for the WWF Intelligence team. “It’s the workshop where you pull everything together.”

Measuring the Imponderables

The definition of spatial finance is broad and can technically apply to any sort of economic indicator that can be measured from space or terrestrial sensors. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some investors relied on satellite imagery of Chinese automobile plants to assess economic activity and adjust investments. Hedge funds have used remote sensing to monitor oil inventory levels, lumber supply, and crop yields.

However, the more innovative application of spatial finance today may be its ability to measure traditionally nebulous environmental outcomes, like the carbon-trapping power of untilled soil or the effect of pollinators—or invasive species—on agriculture or timberland. The WWF and others refer to this narrower scope as geospatial ESG.

Financial institutions—which often invest over decades—increasingly recognize the importance of minimizing methane emissions, habitat destruction, and other activities that harm the natural world and heighten climate risks. Their spatial finance analysts rely on advances in data technology and location intelligence to translate those factors onto the balance sheet—or more accurately, the smart map.

“The ability to assign economic values to things—to positive externalities which before had just been taken for granted—that is a key aspect of this discussion,” says Richard Hall, president of Buckhead Resources, a natural resource management and advisory firm based in Atlanta, Georgia.

For example, S&P Global has used NASA satellite imagery to study public water utilities. Analysts determined that utilities sited near ecosystem resources like evergreen forests had better outcomes on debt metrics. Against the backdrop of droughts and growing water scarcity, that kind of location intelligence can influence credit ratings and municipal debt markets.

The Importance of Self-Monitoring

Business executives are beginning to recognize that their operations and business partners are under scrutiny in ways that were previously impossible.

“There’s a much higher level of scrutiny, particularly in light of the increasing availability of satellite imagery and other remote sensing data,” says Richard Hall of Buckhead Resources. “This may increase risk in some ways, but it also offers significant opportunities to collaborate and improve operations.”

For instance, watchdogs can use satellite-based sensors to track how much methane is emitted from a source, and which company owns that source. Other remote data reveals deforestation and its perpetrators.

Transparency, in other words, is no longer a choice.

“With this remote sensing, different stakeholders are able to call out situations that may warrant action that may have previously gone unnoticed and unaddressed,” Hall says.

Savvy executives will use remotely sensed data and GIS analysis to monitor their own operations and stamp out bad practices before watchdogs do.

Finance is incredibly important to how decisions are made and how the natural world is impacted.

David Patterson, WWF UK Head of Conservation Intelligence

A Dual View on the Value of Sustainability

There’s a longstanding history in natural resource industries of using GIS to manage and track key data and information such as timber inventory or real estate values, says Hall, who also serves as an instructor of natural resource finance at Auburn University. With GIS that uses AI to contextualize satellite imagery and data gathered from sensors, investors, insurers, lenders, and other stakeholders can now take into account what are known as “ecosystem services.”

The term, popularized by the United Nations-sponsored Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, identifies the benefits that society and the planet derive from healthy ecosystems like woodlands, wetlands, coastal reefs, and mangrove forests. Rather than seeing trees only in terms of the dollar value of timber, firms like Buckhead Resources use spatial finance to also quantify a forest’s value as a carbon sink, as a source of revenue from hunting or other recreational activities, or as a natural bulwark that prevents soil erosion.

The dual view afforded by spatial finance helps Hall offer landowners, timber companies, and other clients guidance on complex questions. By analysing metrics like soil and water quality and nearby transportation infrastructure in a geographic context, he can advise a company on how to optimally manage land for a combination of uses including commercial forest management, mining, or conservation. The same analysis can extend to forestry and other natural resource firms that are exploring a transition from land use focused on natural resource management to uses such as real estate development, infrastructure, or renewable energy.

For Hall, who opened his firm just two years ago, GIS’s data and analytical capabilities are the linchpin of spatial finance, and help generate the kinds of insights that might normally come from a much larger firm. “We’re able to do so much more than we could do otherwise by leveraging our abilities with a powerful GIS platform,” he says.

Fine-Tuning the Fleet with AI

One emerging technique for creating efficient EV fleets is the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to improve driving routes. Companies at the forefront of EV adoption are collecting data on driving patterns and analysing it with GIS-based AI technology. An early pilot with a prominent national brand produced smarter routes with lower fuel consumption and less time on the road.

Being able to visualize and effectively manage with a good GIS package is critical. But [just] as important as being able to visualize it [is] integrating that spatial data with the financial data.

Richard Hall, Buckhead Resources

Gaining Visibility on Regulatory Risk

Another area where spatial finance is fast gaining traction is in policing reputational and regulatory risks. Many financial contracts these days include environmental, social, and governance (ESG) guidelines around measures like carbon emissions. For multinational companies and the banks and investors that provide them financing, lack of transparency on supply chain impacts or the actions of business partners can trigger fines and damaging headlines.

“There’s huge demand from financial institutions to better understand what’s going on,” says WWF’s Patterson. “There’s a lot of regulation coming on top of them. They sign up to these agreements and, in many cases, they struggle to understand if they are complying to those agreements.”

For instance, a bank that adopts the Equator Principles, a major benchmark of socially responsible practices for financial institutions, has to consider the impact of loans on critical biodiverse habitats. With a GIS-powered dashboard, bank executives can leverage remote-sensing data to monitor where companies in their portfolio might be operating in proximity to protected sites.

“The smart actors I see now are the ones who are closely watching developments, preparing and building capacity, hiring the right people, and are already there demanding access to asset data and better environmental data,” Patterson says.

To Grow, Protect, and Preserve

It’s telling that many of the places on earth that have the highest levels of biodiversity also tend to be rich in natural resources; healthy ecosystems foster the ideal conditions for natural life, and economic opportunity often follows.

Guided by the geographic context of location intelligence, spatial finance and geospatial ESG help stewards of capital find a balance between capitalizing on earth’s rich bounty and protecting it for future generations.

Three Key Steps to Using EVs in Business

As companies integrate electric vehicles into operations, they'll find opportunities to optimize EV fleets through location intelligence.

Even two short years ago, Ken Crombie couldn’t have imagined piloting an electric vehicle (EV) program for his quickly expanding building supply business. Fast-forward to now, and Crombie’s not only hopeful about piloting electric flatbed delivery trucks equipped with fuel-free forklifts, he’s downright determined to do so.

Article snapshot: Whether a company delivers packages or deploys regional sales teams, electric vehicles will soon play a role. Smart maps help executives manage EV fleets profitably.

“Electrifying the fleet used to be a blue-sky concept, something I assumed only my largest competitors would ever venture into,” says Crombie, who owns and operates a private, third-generation family business just north of the US-Canada border. “All that’s changed. We need to understand what our new obligations will be as the federal government pushes towards net zero. Besides that, I really want our business to be part of the climate change solution.”

At a micro level, industrial companies like Crombie’s are on the front lines of a climate emergency spurring the push for carbon neutrality in North America and beyond. While entrepreneurs and startups fight climate change one EV at a time, larger organisations are exploring the best way to electrify their operations and deploy EV fleets on a grander scale. Regardless of size or scope, common factors connect all organisations charting an electric path, and chief among these factors is location.

“It gets really cold here in winter. Vehicle vendors I speak to are thinking about the temperature at our location as they decide where they’ll test out equipment. They need to know how we’ll house the trucks in winter,” Crombie says. “They also need to understand the terrain we cover. Our delivery trucks navigate urban centres and rural farm fields in the course of the same day. That information is key to our decisions around going electric.”

High-growth family enterprises with green ambitions or global delivery companies launching EV fleets. Ride-share and car rental companies determined to reduce their carbon footprints, or pharma giants working to electrify the way sales reps travel across territories. Whatever the business, and however it’s structured, analysing and operationalising location data will be central to the successful rollout of EV fleets. Tomorrow’s net-zero standouts are already taking this approach, using geographic information system (GIS) technology in three key stages of the process.

-

Map and Analyse Operations before Deploying EV Fleets

Road transportation accounts for 23 percent of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the US today. With the Biden administration pledging to cut GHG at least 50 percent from 2005 levels by 2030, transportation represents a major focus area. Electrifying fleets holds significant potential. In fact, one McKinsey report suggests that by 2030, fleet EVs could have a total cost of ownership 15 to 25 percent less than that of an equivalent fleet of internal-combustion engine vehicles. That’s because the moderate price of electricity and high use of fleet vehicles allow organisations to quickly recoup higher up-front costs.

Like most product or service innovations, companies will roll out their EV fleets in stages; companies will need to analyse where and how the switch to EVs will affect operations and customers. When Amazon, for instance, announced the purchase of 100,000 custom electric vehicles to fuel deliveries, the program kicked off in Los Angeles before expanding to other cities.

Executives have used GIS to analyse business strategies for years—and now fleet planners can enlist the technology’s analytical capabilities to plan a transition to electric vehicles. That includes mapping existing and planned operations to identify the best initial markets for electrification, assessing how many EVs to buy, and determining where to locate them. Whether the company is planning for mobile workers (from package delivery drivers to commercial pest controllers) or for a vehicle-focused business model (think rental car companies), this initial mapping is a chance to examine parameters like topography, population density, brand exposure, and consumer preferences for green business. Such analysis can inform decisions about how best to electrify the fleet.

For instance, EVs on hilly terrain use energy differently from those in flatter areas. Cold climates drain batteries more quickly than warm ones. In rural or remote areas, EVs might have to travel greater distances between customer stops on a single charge. And prospective clients and employees in certain geographies are more likely to consider EV fleet operations an appealing brand differentiator. Those conditions can be analysed with GIS, delivering smart maps that help organisations plot fleet electrification in locations where it’s likely to make the greatest impact.

Critically, GIS analysis can identify the need for new depots, distribution centres, or other facilities by mapping current operations against the charging infrastructure in a given geography. This location intelligence will also help executives map EV fleet expansion plans down the road.

Geographic and environmental context on an EV transition make for stronger strategic plans and better odds that the program will achieve green commitments and bottom-line benefits. The advanced analytics that GIS technology provides connects strategy with execution in ways humans simply cannot.

-

Use Location Analytics to Improve Processes once an EV Fleet Hits the Road

The COVID-19 pandemic didn’t just slow economic activity in 2020—it also drove a 10 percent drop in this country’s GHG emissions. Channeling that momentum into sustained progress will be challenging as the nation resumes pre-pandemic levels of economic activity and energy consumption. But organisations committed to cost savings and net-zero targets can use location analytics to manage and improve EV fleet strategies once they are launched.

Consider rental stalwart Hertz, which recently ordered an initial batch of 100,000 EVs. This massive investment will effectively position Hertz with the largest EV rental fleet in North America. It also demands an extensive network of EV charging stations across the company’s global operations.

For companies in any industry, it’s not enough to invest in electrifying a fleet in the right geography at the right time. Strategic intentions require clear plans, daily management, and continuous optimisation. This is where location data can play a starring role.

By drawing on GIS-backed location intelligence, EV fleet managers can better align vehicle models and charging capacities with planned routes. Location data reveals where and how EVs are navigating the network, pinpointing possible optimisations to where and when they travel. Location intel can also be leveraged to redraw the lines around a sales rep’s territory based on the distance between customers and the nature of the roads, weather, or temperature.

Similarly, a national EV manager might use GIS to identify markets where EVs most often require roadside service, and shift maintenance teams and facilities accordingly. Geographic analysis can highlight regions where there’s a surge of battery replacement requests during winter, a dip in range, or other areas ripe for improvement.

GIS technology also empowers companies to plan; if data reveals that the average EV battery life in a given market is six years, procurement teams can make smart budgeting decisions, planning sell-offs and upgrades well in advance to capitalise on deals and incentives.

Taken together, these capabilities create benefits beyond fleet upkeep, optimisation, and disposal. Grounding fleet management in location analytics generates data that enables the organisation to balance customer expectations, net-zero targets, and bottom-line benefits.

Constraining the Fleet

Companies looking for new ways to optimise their EV fleets may apply a technique called constraint optimisation to GIS maps. This helps planners analyse what-if scenarios: What would our delivery network look like if we prioritised customer delivery times above all other factors? What if our top priority were to minimise greenhouse gas emissions? GIS technology reveals the ideal EV routes and schedules for each scenario.

A GIS-powered dashboard tells a business how an EV fleet is performing under different circumstances so managers can tailor routes or sales regions accordingly.

-

Monitor Continuously and Communicate Clearly

The metrics and analytics culled at every stage of the electrification journey inform future decisions about the fleet—and the story a company communicates to stakeholders.

Coming out of the COP26 climate summit, governments agreed to strengthen national plans for reducing emissions. Against that backdrop, organisations working to electrify their fleets have an engaging environmental, social, and governance story to tell. But businesses can’t communicate net-zero progress without first measuring results.

At rideshare company Uber, drivers of fully electric vehicles are now eligible for the Zero Emissions incentive, which pays out $1 on every trip, up to $4,000 annually. They also earn an extra $0.50 from riders who select Uber Green as their ride option. This is all designed to shift Uber toward a greener fleet. It’s precisely the kind of outcome customers, stakeholders, and regulators are increasingly keen to understand.

Using location intelligence to track where (and by how much) a company reduces its carbon footprint is one way to tell a compelling, data-backed story. Communicating that outcome using smart maps and dashboards provides stakeholders a holistic glimpse into how a business is reducing pollution in specific communities around the world. That GIS-based “show, don’t tell” approach—a capability that leading organisations consider instrumental in stakeholder engagement—helps businesses bolster sustainability ambitions with meaningful results.

With a GIS dashboard or story map illustrating a company’s EV progress, executives can show potential partners the broader economic benefits of building out charging-station infrastructure—and ways to do so with greater equity in mind.

Using clear metrics to illuminate opportunities and reinforce progress transforms any company with an EV fleet into a strong potential partner on important and mutually beneficial initiatives.

Fine-Tuning the Fleet with AI

One emerging technique for creating efficient EV fleets is the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to improve driving routes. Companies at the forefront of EV adoption are collecting data on driving patterns and analysing it with GIS-based AI technology. An early pilot with a prominent national brand produced smarter routes with lower fuel consumption and less time on the road.

GIS technology can act as an agile control tower for an EV fleet, helping managers spot trends across the network.

Where Is the EV Fleet Going from Here?

Without data and insight to support the path toward an EV fleet, good intentions are simply not enough. That’s just as true for the small business or startup looking to make a relatively local impact as it is for the global giant set on transforming the transportation game. Both require the kind of location intelligence that today’s technology provides.

In Canada, factors like climate and temperature will continue to shape decisions on the snow-covered highways and back roads Crombie’s fleet navigates. As it stands, he may need to invest in new warehousing to ensure his yard is prepared to host an EV fleet. “We’re realistic,” he says. “We may have to put capital behind our intentions to really resonate with the kind of supplier who sees our potential for building an electric fleet. That’s okay. We’re in this for the long haul and there will be benefits for the environment, and for our business, if we get this right.”

Like the vehicle suppliers he’s negotiating with now, Crombie recognises that having solid data to plan and measure outcomes will count for a lot. Integrating multiple datasets from different fields, and extracting vital insight, can help organisations move plans for an EV fleet from theoretical to practical. Drawing on location analysis at every stage of the process will ensure bottom-line benefits for the company and the planet.

How Real-Time Location Intelligence is Changing Corporate Security

In an ever volatile world, location intelligence is key to understanding how to mitigate risk.

Companies are thinking differently about resilience and risk, and the daily headlines make clear why.

Article snapshot: A new mentality has pervaded corporate security teams as threats grow more diverse and geographically dispersed—here we explore the new uses of location intelligence to contain risk and strengthen resilience.

As a result of COVID-19, every company, regardless of industry, is aware of its security posture. The founder of a small urban food-delivery business and a Fortune 500 executive with a global supply chain face the same questions: Where are the threats to my personnel and assets, and how can I maintain business continuity?

A decade ago, executives might have struggled to understand their vulnerabilities to climate risk or civil or political unrest. Today, in a fast-moving globalised world, they have to answer for a variety of threats: extreme weather, economic distress, geopolitical ambiguity, terrorism, infrastructure collapse, individual acts of violence, and pandemics. Consequently, C-suite leaders are escalating the priority of corporate security strategies, believing them as essential to a business’s long-term health as growth is.

It’s clearer than ever that prosperity requires newfound resilience.

Seeing the Threat Matrix

Every security threat has a spatial dimension—that’s why a geographic information system, or GIS, has become a key technology for mitigating risk and responding to disruptions.

A GIS map brings instant context, showing stakeholders in real time where risks and vulnerabilities threaten assets, people, and communities in any scenario.

The technology fulfils a centralising role in security, providing a common operating picture of location-specific factors like weather, traffic, social media chatter, and evacuation plans. It can perform tasks as basic as showing which roads are still passable in the midst of flooding, and as sophisticated as showing a real-time view of a corporate campus during an emergency. Perhaps most importantly, location intelligence—geospatial insight that enables better business decisions—helps companies prepare to meet threats before they even arrive.

Corporate Security, Then and Now

Corporate security is practically as old as business itself. The term “riding shotgun” dates back to the days of stagecoaches and highway robbery, when Wells Fargo hired employees to sit upfront in carriages transporting currency, holding a shotgun to deter thieves.

Today, corporate security is harder to define because it encompasses multiple disciplines. Strategically, it covers enterprise risk management: the policies and procedures an organisation deploys to strengthen itself against adverse events. One important example is using location intelligence to ensure that data warehouses and data back-up centres aren’t located in risk-prone areas, like those subject to flooding.

At the operational level, corporate security extends well beyond weather-related events. For instance, the recent spate of flash mob robberies at US retailers has earned the attention of corporate security teams. Other security teams are focused on executive protection—gathering risk intelligence and monitoring where key employees travel around the globe—and special event management.

The objectives and outlook of corporate security teams have changed as well.

In the past, physical security was often the focus—implementing locks and access controls, running security cameras and a CCTV network. Many in the industry came from law enforcement backgrounds, and a castle mentality prevailed—the inclination to raise barriers against possible threats or intrusions.

Today’s security and resilience professionals are more apt to talk about a “threat landscape”—a kinetic, dynamic paradigm in which a bank, for instance, might be vulnerable not only because it stores currency, but because it could be a symbol for non-state terrorists to attack. Accordingly, more people with intelligence backgrounds are entering the field. These professionals are using GIS technology to produce location intelligence that is more proactive than reactive; it helps identify areas at possible risk—from geopolitical, climatological, or other threats; uncover bottlenecks; and inform contingency plans to mitigate adverse effects and enable continuity.

A Changing World

Globalisation is reshaping the breadth and depth of the span of responsibilities for corporate security.

As companies expand into new and more dispersed marketplaces, they increase exposure to a wider array of risks—a concern the pandemic has made abundantly clear—and so they require a robust resilience strategy and high-calibre security professionals to manage it.

Regulatory bodies and insurance and reinsurance organisations have also begun exerting pressure on companies to improve security and accurately assess multiple categories of liabilities in locations around the world. With climate change poised to transform sectors like real estate and agriculture, resilience is becoming a priority for industries that may not have been considered highly vulnerable to risk in the past.

What’s happening today is not unlike the aftermath of 9/11, which also had a resounding effect on how businesses think about threats. The attack helped raise awareness around “black swan” events—highly improbable, difficult to predict occurrences that can cause maximum damage. As a result, business executives have increasingly funded the creation of corporate security centres that are continuously on guard against dangerous developments in the geographies where the business operates.

Centralising Corporate Response to Threats

Large companies in particular are centralising and coordinating responses through a security operations centre (SOC) or global security operations centre (GSOC). These nerve centres monitor operations nationally or internationally around the clock, managing the flow of information and collecting and evaluating data as it pertains to risk. Most operations centres use GIS technology to show the company’s activities in real time worldwide—and create user-defined operational pictures of any activity that needs attention. The centres are similar in function to the state-operated fusion centres formed after 9/11 to facilitate a pull-push exchange of important information between agencies.

Companies often need this calibre of domain awareness because law enforcement may not be able to provide the degree of detail necessary for a corporation to mount the appropriate response to an incident. Operations centre teams can get an understanding of events before they’ve come to fruition or as they’re occurring, and push information up the chain of command more quickly than outside organisations can. This kind of centralised, location-specific intel proved invaluable during the pandemic. Security professionals who had been monitoring storms and other incidents quickly pivoted GIS technology to track and communicate updates on case counts, local shutdowns, and employee health and safety.

Securing Events through Location Intelligence

One of the areas that GIS-equipped security centres have most transformed is special event management.

Employing the latest technologies, a company can have a real-time view both vast and intimate of a large-scale complex event. A smart map or dashboard makes clear the layout of infrastructure like buildings and underground facilities, as well as points of interest like fire alarms and defibrillators, medics and cops, and areas where suspicious activity has been reported.

Layers of information can be peeled back or added as needed. Or security personnel might toggle between hard and soft zones of inner and outer perimeters—focusing, for example, on the neighbourhood surrounding a site to understand the situation better.

Linked up with other platforms, GIS-based analysis can go even deeper.

Professionals in the field carrying out tactical site surveys can update mobile devices to identify points of interest and immediately sync to the common operating picture. Using drones capable of real-time imagery capture, operations teams can quickly enhance a basemap with images of temporary structures like tents or barricades. The use of 3D technology allows for analysis of viewsheds and lines of sight—the ability to determine who can see what and be seen where. GIS visualisations reveal where shade will fall at a given hour, or how far a flood might overrun on a neighbourhood.

Unlike a static security operation plan written on a whiteboard or frozen on paper maps, a location-aware dashboard enables security personnel to be dynamic, responding in real time to where assets and threats are.

Forecasting and Mitigating Extreme Weather Risks

Another area where centralisation and location intelligence have bolstered corporate security is in anticipating and quickly responding to extreme weather events.

When weather disasters strike, each state marshals its own resources and handles its own response. But national or global companies exposed to the same risks may have to respond simultaneously across those locations.

The 2018 flooding through the Ohio River Valley and down the Arkansas River, for example, touched some retailers with a presence from Nebraska down to southern Arkansas.

A major chain with a GIS-savvy GSOC can begin to model the storm even before a raindrop has fallen, forecasting where and what the impacts will be and what precautions should be taken. Those models might show where rainfall could prompt river flooding, illuminate which roads and areas could be affected, and predict other downstream consequences.

The security team can communicate with offices and stores to let them know a bad storm is on its way, and to ready flood mitigation resources. Store staffs can also prepare for surges in activity, including traffic and high demand for certain products.

Beyond ensuring its own business continuity, a security operations centre can use location data to support the community and liaise with state and local government, deploying resources like water or tools to places in need. The effects of weather events tend to radiate outward, putting pressure on communities and areas further afield. People who are evacuating may need to find shelter or temporarily regroup in parking lots. A smart map can identify these areas before the need arises.

The same principles apply with other types of disasters. In the case of an earthquake, a GSOC can overlay shake maps on the company’s network of offices, warehouses, or stores to understand which are affected by an earthquake. Or during a tropical storm, a map with a layer of power outages can contextualise data about facilities and the grid in order for business leaders to make smart, fast decisions.

The Future of Corporate Security

Far removed from the days of shotguns and stagecoaches, the field of corporate security is radically evolving.

We’re already seeing the latest cutting-edge applications, including advances in indoor location tracking that use geomagnetic positioning and the frequency of metals within the building to yield a more accurate picture than ever before.

GeoAI promises to help companies process massive amounts of information with potentially huge benefits for security. Machine learning makes it possible to study millions of pictures and videos and learn to detect anomalies, like too many people crowded in one location, or a fire breaking out. Computers can learn to look for those anomalies in security data and video in the future.

And with new cloud-based innovations, companies that use GIS technology can now practice distributed collaboration. Organisations that traditionally compete to attract customers can now collaborate on security by sharing maps and information related to shared threats.

However sophisticated the technology might become, the fundamental goal of corporate security remains unchanged: to get the best data on which threats exist and where, and put plans in place to mitigate risk and maintain business continuity.