In the fall of 2018, Bill Kennedy was logging 25,000 to 30,000 steps per day on his Fitbit. That’s an impressive tally under any circumstances, but Kennedy was walking most of those miles on a mountain. The director of land development at Vail Ski Resort in Colorado had spent nearly four decades planning chairlifts, trails, and restaurants at North America’s most popular ski resort, but he had never encountered a project of the scope and urgency he was now facing.

“For [this] size project, a lot of us were skeptical, including myself,” Kennedy says.

The challenge was an epic snowmaking expansion—reportedly the largest in the ski industry. If it had any hope of success, Kennedy and others at Vail would need strong legs, cutting-edge technology, and a close partnership with a mapmaking colleague. But at the outset, no one was sure that would be enough.

Article snapshot: Determined to deliver early-season openings to thousands of skiers, management at Vail Ski Resort initiated an expansion of its snowmaking capabilities that relied on a digital twin of the mountain’s infrastructure. But even the team working on the expansion wasn’t sure it would happen in time.

The Business Challenge of Nature’s Whims

By skiing standards, Vail is massive. It’s the second-largest single-mountain operation in the United States, spanning more than 5,300 acres. (For comparison, the Northeast’s largest resort covers 1,500 acres.) Vail boasts nearly 200 trails, and its 32 lifts can move 63,000 people every hour.

Much like Vail Mountain itself, the international business behind it is a vast operation. Vail Resorts owns more ski destinations than any company in the world, and its network includes coveted retreats like Colorado’s Breckenridge, Utah’s Park City, British Columbia’s Whistler, and Vermont’s Okemo. Holders of the company’s Epic Pass can resort-hop their way through winter.

Vail’s Rocky Mountain location is a snowy oasis averaging 350 inches a year. Unfortunately, businesses don’t run on averages, and at Vail as at most ski resorts, accumulations can vary widely year to year. During the 2018–19 winter, the mountain saw 281 inches of natural snow. Two years earlier it received just 171. The season’s first flakes might fall in October, November, or even December.

Executives in any business can appreciate the downside to that variability. For ski resorts that operate only part of the year, a predictable and early opening to the season has direct impacts on the bottom line. Resorts that can open four or five weeks before natural conditions would normally allow it can extend their season by 25 percent or more and gain a commensurate revenue boost.

In 2018, Vail’s management decided to fund a snowmaking expansion to improve their odds of delivering the early-season openings guests crave. Kennedy calls it “one of the largest single-year expansions that any ski area has taken on in the world,” an assessment he heard from the vendors who installed the equipment. On order: 19 miles of pipes for air and water, 25 transformers, 421 snow guns, and more. The timeline: have the new snowmaking operational before the 2019 ski season.

Recalling the schedule, Kennedy admits, “We were probably a little bit late getting into the game in the fall of 2018.”

When executives announced the project, the man who had been quietly mapping Vail’s infrastructure was ready.

An Unexpected Path to the Slopes

Mike Krois never dreamed of working on a mountain. He spent his childhood in flip-flops in the desert near Sedona, Arizona, and whenever he imagined his future, it looked sunny and warm. But after graduating from Arizona State University with a degree in economics and not much of a plan, he moved to Vail, a town of fewer than 6,000 residents that attracts more than a million visitors each year.

There, Krois launched a career in the aviation industry, eventually working in locations around the world as a dispatcher for a charter airline. Wherever he went, maps piqued his attention. He collected ski trail renderings and spent countless hours in planes, puzzling over the terrain below.

In 2015, he channeled that interest into a master’s degree in geographic information system (GIS) technology from the University of Denver. Soon after, he took a job at Vail Ski Resort, and found that the concept of location meant different things to different people on the mountain.

“[Ski] patrol has their own terminology, grooming has their own words, snowmaking [too],” he explains.

Ski patrollers would tell Krois over the radio that they were standing near 2903. His response was always the same. “‘You’ve got to tell me what chairlift you’re by, because I don’t know where 2903 is. It’s the old phone that used to be there 20 years ago.’”

To Krois, the situation was clear. Like many businesses that manage physical facilities, Vail’s teams were hamstrung by location folklore, a charming but inefficient way of communicating where assets are and where employees need to be. What they needed was location intelligence. Krois set out to create a common language, and put Vail on a new kind of map.

The ski industry has only just begun to see the value in GIS. People just don’t know what they don’t know. But once you show them what can be done, it can open doors.

Mike Krois, Vail GIS analyst

Creating the Mountain’s Digital Twin

Beginning in 2016, Krois’s challenge was to map the mountain—in essence, to create a digital twin that operational teams and executives could rally around. In part, that meant capturing the knowledge of mountain veterans like Kennedy, who knew the history hidden beneath the snow.

Mike Krois uses a GPS unit to create accurate measurements for Vail's digital twin.

Skiers, snowboarders, and mountain bikers rarely think about the hardware buried safely under their feet. But that infrastructure—including the electrical, water, and air lines that power chairlifts and snow guns—is the circulatory system of the business. Historically, it hadn’t been well documented.

“Decades ago, it was never a thing to track what we did,” Krois explains. “You’d just bury that pipe and move on. A lot of my job was, ‘Go talk to the old operator who did that 25 years ago. He probably has an idea of what happened, and we need to document it and map it.’”

Working with veterans like Kennedy, Krois created the beginnings of the mountain’s digital twin, capturing asset locations in a database and leveraging the ability of GIS technology to create replicas of both natural and built environments. He then used GIS to generate smart maps for employees. Kate Schifani, who runs Vail’s snowmaking operation, says the maps—and the common language they created—have been a boon to her team.

“It really helps with our learning curve for brand-new snowmakers,” she says, “because you can send them out there, and they’ve got the map on their phone, and we can say, ‘Go down this line.’”

“It sounds simple,” Krois adds, “but it goes back to efficiencies. It gets these people up to speed really fast.”

As Krois’s digital-twin work progressed in the back half of 2018, Vail executives approved the massive snowmaking expansion that they hoped would deliver consistent early openings and longer seasons. It was a major investment, and management wanted it done in record time. With hard work and location intelligence to guide them, Kennedy, Krois, and Schifani had a shot at success.

A Business Investment in Predictable Openings

Unlike ski resorts in the eastern US that must make snow all winter, Vail’s snowmaking season starts early and ends by mid-January, when natural snowfall and cold temperatures take over.

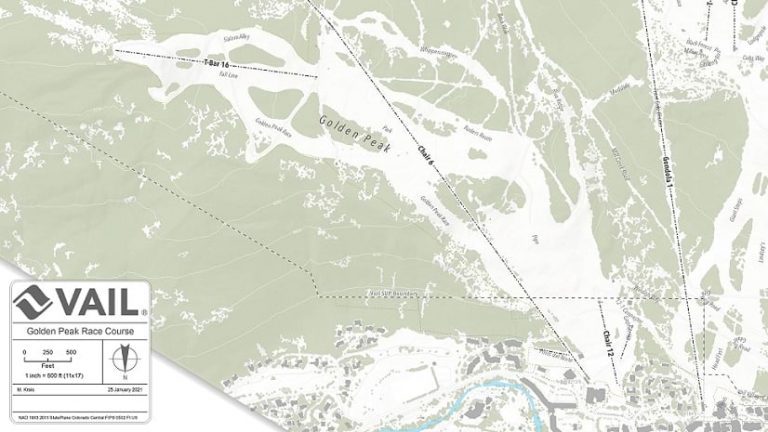

A GIS map of Vail Ski Resort sets the foundation for the mountain's digital twin.

The aim is to open the resort in November—often before Thanksgiving. To make that happen, Schifani’s team operates in two 12-hour shifts from October to January. “Without snowmaking, we would still have a great ski season,” she says. “But this year, for example, we would have a great ski season five weeks later than we had thought we would.”

In 2018, Vail’s snowmaking capacity was concentrated near the mountain’s midsection, on trails that were subject to sun exposure and lacked beginner runs. Vail executives focused the snowmaking expansion at the top of the mountain—around 11,000 feet, where temperatures can be 8 to 10 degrees colder, holding snow through the winter. (Counterintuitively, the higher elevations also host beginner trails, which meant Vail could accommodate a broader range of guests earlier in the season.)

That August, Krois huddled with Vail’s planning and operations teams to map the massive expansion in GIS. With digital maps projected on big screens, they plotted where pipes would run and where snow guns would sit along the trails—creating a system that would return at least 75 percent of the water it used to the local watershed. Kennedy describes the weekly meetings as “20 people talking about what was going on and making adjustments on the fly, with Mike sitting there and making those changes.” Kennedy adds, “I’m not a real technology guy, but when it does the things that I saw it doing, I become a believer.”

With the digital plan in place, it was time for a reality check.

Walking the Mountain as the Clock Winds Down

Map Powers a Digital Twin in the Control Room

When Mike Krois captured Vail Ski Resort’s assets and utilities in GIS technology, he essentially created the digital twin for a sophisticated system of automation.

In Vail’s control room, a manager constantly monitors that digital twin—a map of the mountain’s compressors, pumps, water and air valves, snow guns, and other hardware involved in the mountain’s maintenance.

Occasionally the control room manager clicks a mouse to adjust water flows or start snow guns.

“Anytime we’re turning things on from the system, it’s basically off the map that Mike gave them,” explains Kate Schifani, Vail’s snowmaking manager. “So you can graphically see what hydrants are green—lit up—so I know what’s running.”

Throughout the winter, the snowmaking team adds notes to GIS smart maps, creating a road map for maintenance.

“We can go through and see, okay, I’ve got a couple ball valves that we’re going to replace when it gets warm,” Schifani says. “We’ll save that for the summer, and then we’ll go investigate. It’s super easy just to be able to see that and see it where it is on the hill.”

“As much as I try to make it a science to plot out where we put these fans,” Krois says, “it’s equal parts art, because . . . the winds at one area may blow out of the northwest, and then 100 feet up they may blow out of the southwest.”

Determined to blend those subtleties with science, the GIS analyst and the Vail veteran walked the mountain together. Krois used a handheld GPS device to identify the snow gun locations they had planned in the office, and Kennedy used his decades of experience to make tweaks that would ensure skier safety and give Schifani’s team the best chance of making the most snow.

Soon after Krois and Kennedy finished the updates, winter buried Vail Mountain in its splendor. When spring 2019 dawned, the pair began walking the hill again, this time consulting the project’s GIS-based digital twin. Along the way, they drove stakes into the ground to indicate where each new piece of infrastructure should go.

By late spring, all that was left to do was install 19 miles of hardware in the ground, capture every piece’s coordinates in GIS, and open the new-and-improved Vail six months later.

That phase of the project drew on a trusted slate of outside companies—engineers, construction teams, power specialists, and more. As the contractors poured in that spring and summer, digging trenches, burying hardware, and connecting systems, they were guided by the location intelligence Krois had captured in the project plan. Kennedy says the digital tools made a difference.

“The time that we’re saving is immense with the technology,” he says.

As summer 2019 turned into fall, the fickle Colorado skies dealt Krois and the team one final test. Krois was on the mountain with the contractors, capturing GIS data.

“We’re literally installing the last pump house,” Krois recalls, “and it is dumping snow. [We’re] down to the wire getting the system put together.”

With management on edge and thousands of skiers looking forward to opening day, the stakes were high.

“Everyone was holding their breath that we’re going to do this,” Krois says. “And we did.”

When the new system came to life, Kennedy felt a surge of excitement. “This was really a big step for the company and for Vail Mountain,” he says.

Our goal is to use all this technology and make it ultimately easier for us when we're building [the snowmaking system], but [also] easier for the operator to run and operate and visualize and maintain all this equipment long term.

Bill Kennedy, Vail director of land development

Leave the Snowcat, Take the Shovel

The project paid off handsomely that season, and even more so the next. As November 2020 approached, Vail’s executives and operations managers faced a pandemic and a drought. The expanded snowmaking capacity helped them address both.

Through the work of Schifani and her team, Vail opened in November with 200 acres of terrain—more than double its previous early-season capacity. The extra territory was timed well for the era of social distancing, allowing skiers and riders to spread out.

“None of that would have happened on natural snowfall this year,” she explains.

The mountain’s digital twin has also made everyday operations much more efficient for Schifani’s team. During the first week of January, snowmakers realized air wasn’t reaching a set of snow guns. The team needed to manually open a valve housed inside a vault buried underground beneath six feet of snow.

“None of us knew exactly where that vault was,” Schifani says. “If we didn’t have that [mapping] technology, our options basically would have been to get a snowcat and doze out a 30-by-30-foot section of this run.” Then they would have had to painstakingly probe 900 square feet of earth until they struck the vault.

Instead, they used GIS data to identify the vault’s exact location, and quickly accessed it without disrupting the adjacent trail or wasting hours. “It’s way easier to go, “Oh, it’s right here, get the shovel.’” Schifani explains. “Our technology saved us there.”

Schifani’s take on location intelligence: “We use it every day. I don't want to think about having to do this job without it.”

Kate Schifani, Vail snowmaking manager

Hard Work and Technology Drive Success

Everyone involved in Vail’s snowmaking expansion knew the scope and urgency of the challenge, and worked tirelessly to achieve it. Even so, those closest to the project, including Krois, Kennedy, and Schifani, seem convinced that their effort alone wouldn’t have been enough, if not for the location technology supporting them.

Indeed, it’s hard to imagine asking a contractor to install equipment somewhere near a phone that no longer exists. Communicating through maps informed by a digital twin of the mountain helped the Vail team and its partners meet a major business milestone with unprecedented speed.

“We wouldn’t have been able to make that plan without the map that basically showed us this is what you need to do,” Schifani says. “But we did, which is great. Because it was an awesome opening.”

This article was originally published in the global edition of Wherenext